Teotihuacan: “the place of those who have the road of the gods.”

Teotihuacan, “The City of the Gods”, is a mysterious place on Earth. Everything connected with Teotihuacan is shrouded in the greatest mystery yet to be solved.

Teotihuacan is an ancient city and an ancient civilization.

The name Teotihuacan was given by the Nahuatl-speaking Aztecs centuries after the fall of the city around 550 CE.

The term has been glossed as “birthplace of the gods”, or “place where gods were born”, reflecting Nahua creation myths that were said to occur in Teotihuacan.

Nahuatl scholar Thelma D. Sullivan interprets the name as “place of those who have the road of the gods.” This is because the Aztecs believed that the gods created the universe at that site.

The origins of the city are a mystery. The origin and language of the Teotihuacanos are unknown.

Teotihuacan was one of the first great cities in the Western Hemisphere, and one of the largest cities in the world at that time. At its apogee (around 500 AD), Teotihuacan covered an area of about 8 square miles (21 square kilometers) and supported a population estimated at 125,000-200,000.

The area was settled by 400 BCE, but it did not experience large-scale urban growth until three centuries later, with the arrival of refugees from Cuicuilco, a city destroyed by volcanic activity. It is not known whether the basic urban plan also dates to that time. About 750 CE central Teotihuacán burned, possibly during an insurrection or a civil war. Although parts of the city were occupied after that event, much of it fell into ruin. Centuries later the area was revered by Aztec pilgrims.

The city is considered to be built by hand more than a thousand years before the swooping arrival of the Nahuatl-speaking Aztec in central Mexico. The Aztec, descending on the abandoned site, no doubt fell awestruck by what they saw.

The city had thousands of residential compounds and scores of pyramid-temples … comparable to the largest pyramids of Egypt.

Evidence of a king or other authoritarian ruler is strikingly absent in Teotihuacan.

Contemporaneous cities in the same region, including Mayan and Zapotec, as well as the earlier Olmec civilization, left ample attestations of dynastic authoritarian sovereignty in the form of royal palaces, ceremonial ball courts, and depictions of war, conquest, and humiliated captives.

However, no such artifacts have been found in Teotihuacan. Many scholars have thus concluded that Teotihuacan was led by some sort of “collective governance”.

“Teotihuacan, which contains a massive central road (the Avenue of the Dead, the name was given later by the Aztec) and buildings including the Temple of the Sun and the Temple of the Moon, has no military structures,” says George Cowgill, an archaeologist at Arizona State University and a National Geographic Society grantee.

Who built Teotihuacan?

Scholars once pointed to the Toltec culture.

Others note that the Toltec peaked far later than Teotihuacan’s zenith, undermining that theory. Some scholars say the Totonac culture was responsible.

No matter its principal builders, evidence shows that Teotihuacan hosted a patchwork of cultures including the Maya, Mixtec, and Zapotec.

Although it is a subject of debate whether Teotihuacan was the center of a state empire, its influence throughout Mesoamerica is well documented.

Evidence of Teotihuacano presence is found at numerous sites in Veracruz and the Maya region. The later Aztecs saw these magnificent ruins and claimed a common ancestry with the Teotihuacanos, modifying and adopting aspects of their culture.

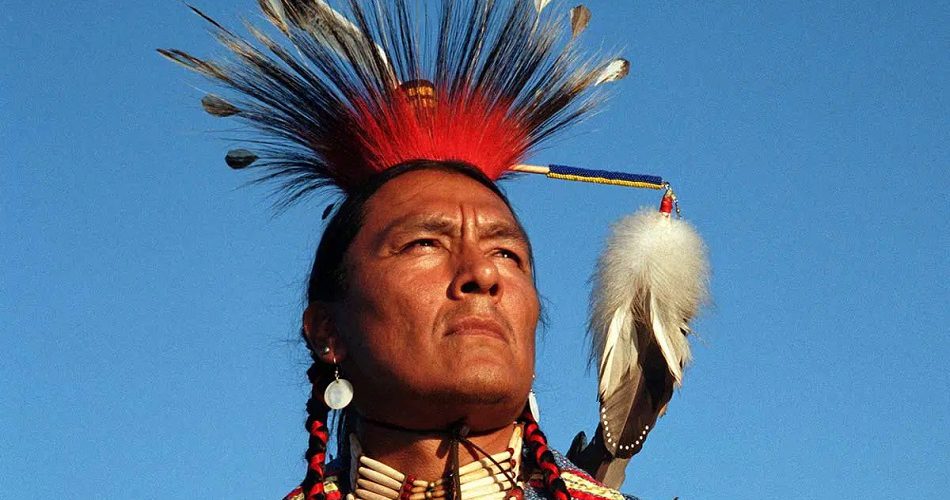

The ethnicity of the inhabitants of Teotihuacan is the subject of debate. Possible candidates are the Nahua, Otomi, or Totonac ethnic groups. Other scholars have suggested that Teotihuacan was multi-ethnic, due to the discovery of cultural aspects connected to the Maya as well as Oto-Pamean people. It is clear that many different cultural groups lived in Teotihuacan during the height of its power, with migrants coming from all over, but especially from Oaxaca and the Gulf Coast.

Majestic even in its ruins, the city impresses with its indescribable grandeur.

Cowgill says the site’s visible surface remains have all been mapped in detail, though only some portions have been excavated.

In addition to some 2,000 single-story apartment compounds, the ruined city contains great plazas, temples, a canalized river, and palaces of nobles and priests.

The main buildings are connected by a 130-foot- (40-meter-) wide road, the Avenue of the Dead (“Calle de los Muertos”), that stretches 1.5 miles (2.4 km). Oriented slightly east of true north, it points directly at the nearby sacred peak of Cerro Gordo. The Avenue of the Dead was once erroneously thought to have been lined with tombs, but the low buildings that flank it probably were palace residences.

The north end of the Avenue of the Dead is capped by the Pyramid of the Moon and flanked by platforms and lesser pyramids. The second largest structure in the city, the Pyramid of the Moon rises to 140 feet (43 meters) and measures 426 by 511 feet (130 by 156 meters) at its base. Its main stairway faces the Avenue of the Dead.

Along the southern part of the avenue lies the Ciudadela (“Citadel”), a large square courtyard covering 38 acres (15 hectares).

Within the Citadel stands the Temple of Quetzalcóatl (the Feathered Serpent) in the form of a truncated pyramid; projecting from its ornately decorated walls are numerous stone heads of the deity. The temple walls were once painted in hematite red.

Excavations of the Citadel were first carried out during the period 1917–20. Individual burial sites were found around the temple in 1925. Carbon-14 dating indicated that the graves were prepared about 200 CE.

The Pyramid of the Sun is one of the largest structures of its type in the Western Hemisphere. It dominates the central city from the east side of the Avenue of the Dead. The pyramid rises 216 feet (66 meters) above ground level, and it measures approximately 720 by 760 feet (220 by 230 meters) at its base.

During hastily organized restoration work in 1905–10, the architect Leopoldo Batres arbitrarily added a fifth terrace level to the structure, and many of its original facing stones were removed. In the early 1970s exploration below the pyramid revealed a system of cave and tunnel chambers. Over subsequent years, other tunnels were revealed throughout the city, and it was suggested that much of the building stone of Teotihuacán was mined there.

The city was initially excavated in 1884. In the 1960s and ’70s the first systematic survey (the Teotihuacán Mapping Project) was led by the American archaeologist René Millon, and hundreds of workers in 1980–82 excavated under the direction of the Mexican archaeologist Rubén Cabrera Castro.

Work in the 1990s focused on the city’s subterranean tunnels and on the apartment compounds, which were found to be decorated with vividly painted murals.

It’s unclear why Teotihuacan collapsed; one theory is that poorer classes carried out an internal uprising against the elite.

For Cowgill, who says more studies are needed to understand the lives of the poorer classes that inhabited Teotihuacan, the mystery lies not as much in who built the city or in why it fell.

“Rather than asking why Teotihuacan collapsed, it is more interesting to ask why it lasted so long,” he says. “What were the social, political, and religious practices that provided such stability?”

Like many of the archaeological sites in Mexico, Teotihuacán guards secrets we have yet to unravel.

By Gilbert Castro | ENC News