Augustus Pugin: creator of Britain’s most iconic buildings

The skylines of Britain’s great cities, London, Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Cardiff, are dominated by two great architectural styles, which compete with one another for the attention of the visitor: the “Gothic,” and the “Classical.” Whilst some really significant buildings (Westminster Abbey, York Minster, the Cathedrals of Salisbury, Winchester, Ely and Durham prominent among them) are genuinely Gothic (i.e. Medieval), none are genuinely Classical (i.e. Roman – this is in contrast, say, to France, where significant Roman buildings are still standing). Most of the prominent buildings in British cities are more accurately described as “Neo-Gothic” or “Neo-Classical,” and were built in the Seventeenth, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.

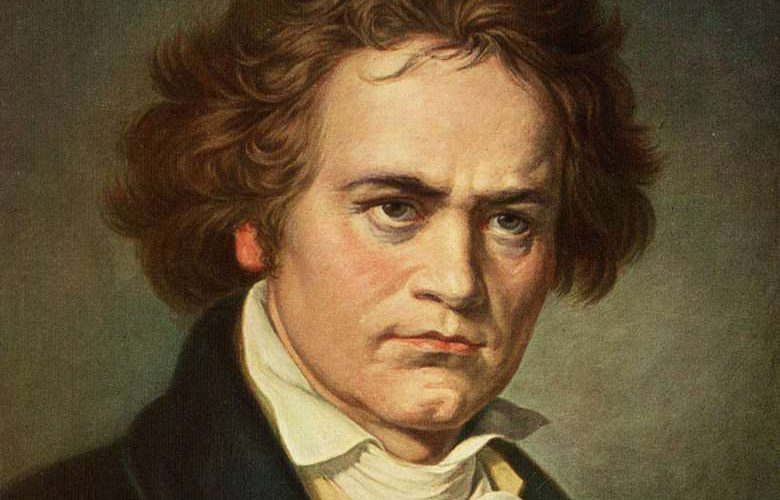

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852) was one of the leading architects of Victorian Neo-Gothic. He was not the first British architect of the modern era to look to the Medieval past for inspiration, but he took the attachment to the Gothic world view to a new level, and, in doing so, created some of Britain’s most iconic buildings.

Pugin’s father, A.C. Pugin, himself an architectural illustrator, came to England as a refugee from the French Revolution. As a boy, Augustus travelled through Germany and the Netherlands with his father, helping to survey and sketch the great Gothic churches and cathedrals of the continent. By the age of fifteen, he himself was designing Gothic furniture for Windsor Castle.

Pugin’s great break came in 1834, when a fire destroyed the greater part of the Palace of Westminster. A committee was established to commission a replacement, and the contract went to Pugin’s collaborator, the architect, Charles Barry. The committee had specified that the new building should be either in the Gothic or the Elizabethan style: the capital already had its share of Neo-Classical buildings – Somerset House, St Paul’s Cathedral, the Greenwich Hospital, the British Museum, still under construction – and the style had been discredited by association with the nation’s defeated enemy, Napoleon Bonaparte. Britain was not a secular republic, it was argued, but a Christian kingdom, and this identity should be reflected in the nation’s most prominent public building. Pugin argued, successfully, for a Neo-Gothic building, not least because one of the few surviving elements of the original Medieval building was Westminster Hall, built during the reign of Richard II.

Arguments have subsequently raged over which man was responsible for which elements of the building, but it seems likely that, whilst Barry designed the floor-plan and managed the budget, Pugin took responsibility for much of the detail, including the design of what is now referred to officially as the Elizabeth Tower (but, popularly, as “Big Ben” – actually the name of the bell), and almost all the features of the interior.

For Pugin, however, the choice of Gothic was not simply an aesthetic, but also a moral, even a religious one. In 1836, he converted to Roman Catholicism, and, in the same year, he published a tract called Contrasts, arguing that the Gothic was the authentic Christian style, which embodied the principles of true religion. Classicism, on the other hand, he saw as rationalistic, atheistic, and ultimately utilitarian, going hand in glove with the tendency to treat human beings merely as means to an end. His tract came with a series of provocative illustrations.

As a refugee, Pugin’s father had adopted the Anglican faith to avoid the prejudices that might have prevented him from finding work. During the reign of Queen Victoria, however, Britain became more tolerant of other religious traditions, including Catholicism and Judaism. The Catholic Church re-established a hierarchy of bishops, and new Catholic churches sprang up around the country, largely in response to the influx of Catholic, Irish labourers. Pugin was well-placed to be the architect of preference to the new dioceses, although he sometimes came into conflict with the bishops, both over budgets (like many architects, he didn’t like working within them), and over his ultra-traditional views on church architecture.

Pugin did not only design public buildings and churches, however, but also private houses, schools and colleges.

He died at home in Ramsgate at the age of just forty, and is buried nearby, in St Augustine’s Church, which he designed himself.