It’s a Bad Time to be a Big Jet

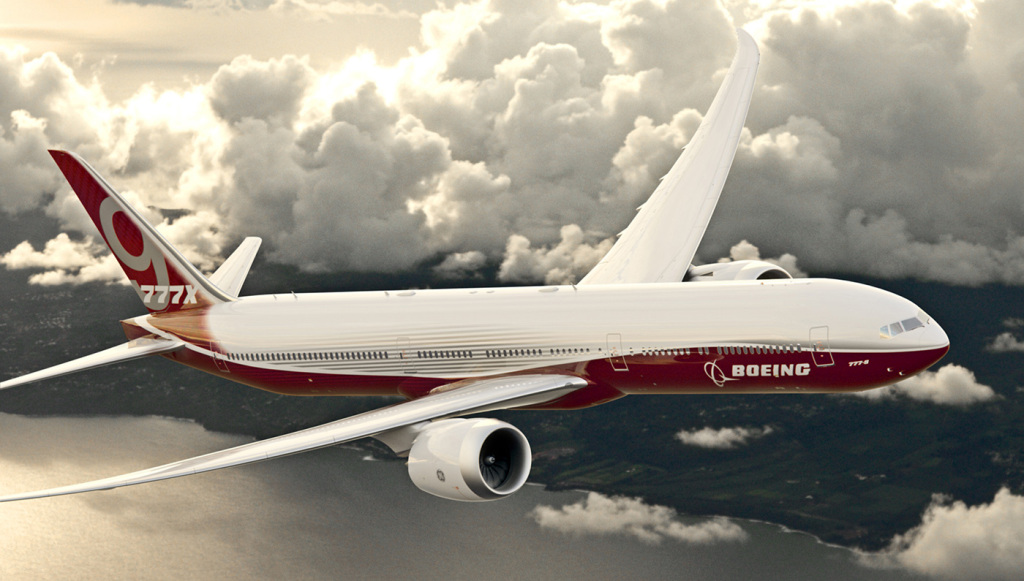

For the better part of a decade, the skies have grown increasingly unfriendly, even hostile to jumbo jets such as Boeing Co.’s 747 and Airbus SE’s A380. Now the fuel-efficient planes intended to replace those behemoths are also encountering resistance. Interest in Boeing’s 777X, a revamped version of its biggest wide-body set to begin deliveries in 2020, is flagging. And in recent weeks, United Airlines and Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd.together have scratched 41 orders for the Airbus A350-1000, a twin-aisle plane designed to carry about 370 passengers, leaving Airbus with only 171 orders for the model.

The problem is that jet fuel is cheap—$550 per metric ton, down 40 percent from 2014. At that price, it’s profitable for an airline to continue operating older wide-body models that launched in the 1990s, such as the Airbus A330 and Boeing’s original 777, and delay purchases of more efficient planes like the A350—which has a fuselage and wings made from lightweight carbon fiber. Even if crude prices rebound, sales of the big jets might not fully recover, say analysts.

That’s because airlines are shifting from channeling traffic through megahubs toward nonstop routes between second-tier cities using smaller twin-aisle planes.

Boeing’s 777X, the company’s biggest two-engine plane, featuring a newly designed wing made from composites, can seat as many as 425 passengers. The deluge of deals when the model was introduced in 2013 has slowed to a trickle, with only 20 of the 326 orders coming since 2015. While no carrier has scrapped 777X contracts, Deutsche Lufthansa AG Chief Executive Officer Carsten Spohr has said his company’s 20-plane deal may be too big and he might delay some deliveries.

For now, the move away from the A350 has given a lift to the A350-900, a slightly smaller variant designed to carry 325 passengers. While about 80 deliveries of that plane have been delayed this year, Airbus has 679 firm orders, or about four times what it’s received for the larger version. The company says its assembly line can easily shift between the two models. United switched from 35 A350-1000s to 45 of the smaller plane—worth $1.4 billion extra at list prices, though airlines always get a discount. United has said it may replace 55 777s with the A350-900.

Despite airlines’ wariness, neither Boeing nor Airbus wants to risk ceding sales of the largest wide-bodies to the other. Until Airbus came out with the A380 double-decker, Boeing’s 747 had ruled the market for jumbos. In the slightly smaller wide-body category, the 777 was long the winner, with the 787 Dreamliner—the first composite jet—slotting in below it. Airbus responded with the A350 and an upgrade of the aging A330. Smaller twin-aisle planes got a further boost Thursday when Turkish Airlines said it had agreed to buy 40 787s, a deal valued at almost $11 billion at list prices. The carrier had considered 747s or A380s, but decided those models were too big.

A potential bright spot for both plane makers is China, where jet travel is growing fast and airlines don’t have many large twin-aisle planes.