Perfect harmony inseparable from divine beauty and celestial purity: Sandro Botticelli, a genius in painting (1445 – 1510)

Sadro Botticelli (real name Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi), an Italian artist of the early Renaissance, is widely regarded as one of the greatest painters in Western art.

Botticelli blended colour, form, and perspective to produce religious and secular works with outstanding visual poetry. Reinterpreting and intertwining traditional imagery from classical mythology and Christian art, his paintings are often open to multiple interpretations.

Early Life

Botticelli was born in Florence. The future artist’s first work experience was as an apprentice to a goldsmith. As a teenager, Botticelli then trained as a painter in the workshops of Florentine artists. Sandro was likely at one of the workshops when Leonardo da Vinci was there. The result of these formative years was that Botticelli’s work displays a concern with graceful figures and capturing ornamental detail. An excellent example is the 1470 CE Fortitude.

Fortitude (1470)

An Established Artist

Already by 1470 Botticelli was established in Florence as an independent master with his own workshop. Absorbed in his art, he never married, and he lived with his family. The artist was popular and mixed public works with private commissions, especially for the powerful Medici family of Florence. For the latter, Botticelli explored many themes from Roman and Greek mythology such as the Primavera (1482 CE). Religious works were not abandoned and he attracted the admiration of Pope Sixtus IV who commissioned Botticelli to decorate a part of the interior of the Sistine Chapel in Rome in the early 1480s CE. The chapel benefitted from the attention of many great artists, and Botticelli was given a lower wall space to show scenes from the Old Testament, which include the Life of Moses panel. He was able to integrate figure and setting into harmonious compositions and to draw the human form with a compelling vitality.

Life of Moses (1481-82)

Portraits

Botticelli had a large workshop in Florence and produced all manner of works. The artist’s private devotional paintings were especially popular. An example of this genre is the Madonna of the Pomegranate (c. 1487 CE).

Madonna of the Pomegranate (c 1487)

Botticelli’s skill at capturing the individual character of faces can be seen even in his larger composite works where background figures stand out as impressive portraits in their own right. An excellent example of this attention to background detail can be seen in his c. 1475 CE Adoration of the Magi.

Adoration of the Magi (c 1475)

Later Career

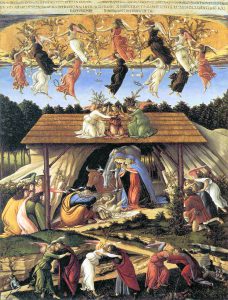

In the 1490s CE Botticelli famously produced illustrations for the Inferno section of Dante Alighieri ‘s literary masterpiece the Divine Comedy. Botticelli was greatly influenced by the ideas of the theologian and preacher Girolama Savonarola, who was an outspoken critic of what he saw as the decline in morality and neglect of religion in Florence and elsewhere. Botticelli was thus inspired to concentrate thereafter on religious paintings. The powerful yet enigmatic Mystic Nativity (1500 CE), with its message that rulers should heed the dangers of a disconnected secular world, is a typical work of this period.

Reputation & Legacy

Botticelli was in constant demand throughout his career. He was recognised in his own lifetime as a genius of painting. Technically excellent at capturing anatomy and perspective, as well as being a master of all types of colouring, the artist’s work was most admired for its overall harmonious effect. Botticelli was also a master of capturing emotions, see, for example, the face of Mary Magdalene in his 1490-2 CE Lamentation over the Dead Christ.

Masterpieces

Mystic Nativity (1500)

The Mystic Nativity is tempera on canvas and measures 108.5 x 75 centimetres (42.5 x 29.5 inches). The painting is now in the National Gallery in London. On the surface, it is a traditional nativity scene, at least across its central band, with shepherds and kings visiting the newborn Jesus Christ in a stable. The top and bottom of the painting are, though, very different. Angels seem to dance in a golden circle above the stable, while below it there are three more angels, each one embracing a man. There are also a number of demons who seem to be at a loss what to do amongst all this joy.

The picture is topped by an inscription in Greek which states that Botticelli made the work in 1500 CE and is living through ‘the second woe of the Apocalypse’ (Rundle, 56), a reference to the gloomy predictions on humanity’s demise that Savonarola declaimed from his tribune. The overload of angels in the painting could even be a reference directly to Savonarola whose nickname was ‘the angelic one’. Yet again, then, Botticelli is combining traditional imagery with his own unique ideas to suspend reality and give his work multiple avenues of interpretation, a classic feature of the best of Renaissance art.

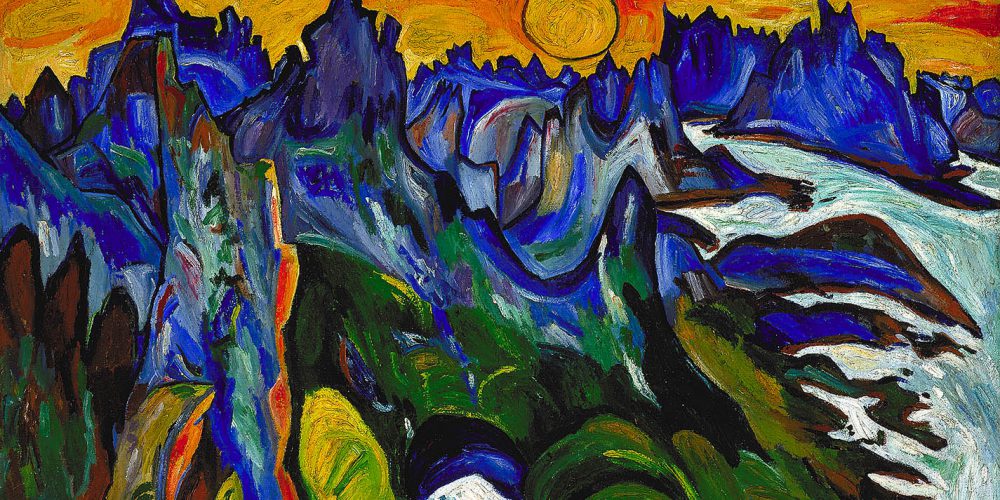

Primavera (1477-82)

The Primavera painting, meaning Spring, has puzzled art historians for centuries as opinions vary wildly on its precise meaning. The painted wood panel was perhaps commissioned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici and completed around 1482 CE. It is a large piece, measuring 315 x 203 centimetres (124 x 80 inches). The identity of the central figure with a red cloak, the presence of what could be the Three Graces or the Hours, and the figure of a shady character dragging off a young woman on the far right of the picture are all particular points of debate as to their significance in relation to each other and the work’s title.

The central lady is most likely Venus given the presence of a cupid above her, but the halo that surrounds her head, formed by the gaps in the bushes behind her, may indicate this is the Virgin Mary or perhaps an amalgamation of the two. The Three Graces of Greek mythology would be an appropriate interpretation of the dancing trio since they were associated with Aphrodite/Venus and spring flowers. The dark blue ghostly figure on the far right may be a representation of the wind god Zephyrus who is abducting what must then be the spring nymph Chloris. The figure on the far left picking an orange may be the messenger god Hermes/Mercury, who also represented fertility. The whole purposely artificial scene resembles a tapestry, particularly given the flowers in the foreground and the orange grove behind and above the human figures, who do not interact with each other at all. An additional clue to the painting’s significance may be in the commissioner, who was that year to be married to Semiramide d’Appiano. Perhaps, then, the painting is an allegory of marriage and the spring honeymoon that follows such a union.

Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c 1490)

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ is tempera on panel and measures 140 x 207 centimetres (55 x 81 inches). The theme of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ captures a very human moment, in which the friends and mother of Jesus weep and cry out all their pain before the body of the Crucifix.

Botticelli sets this in front of the sepulcher to push towards the observer the sound of the silent crying of the people who complain about the body of Jesus. No one screams, in the framework of Botticelli. It is a silent and respectful pain. Christ is supported by the Madonna, who faints because of the pain in the arms of John the Evangelist. Together with her and the disciple are three women, the three Maries. Two of them hold Christ’s body: Mary Magdalene blends her head with that of Christ, in a kiss; another Mary caresses the feet of Christ, with her hands and her hair; the third, in the background, suffocates her tears in the mantle, covering her face. We can only see her eyes, very serious and full of pain as they observe the three nails extracted from the Cross, still full of the blood of Jesus.

Botticelli also seems to insert a reason for hope: the rock wall of the sepulcher is already broken by the earthquake which broke out after the Crucifixion. This detail already heralds the resurrection, together with the soft grass, in which the group of figures walks. Grass absent inside the cave is a fragile sign of rebirth, in which Botticelli gives us hope that death is not the last word.