The life-giving power of art: Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo is one of the most illustrious Spanish Baroque painters.

Murillo, whose most famous works include the Soult Immaculate Conception and the Vision of Saint Anthony, is believed to have been born at the end of 1617, and baptised on January 1, 1618.

Murillo first learned from his distant relative Juan del Castillo, also a Baroque painter.

In the 1640s, Murillo travelled to Madrid, where he learned from Diego Velázquez, one of the leading figures of the Spanish Golden Age who was once King Philip IV’s court painter.

From Madrid, Murillo studied the works of Italian and Flemish painters, including Anthony van Dyck and Jusepe de Ribera.

After going back to his native town of Seville, Murillo painted 11 pictures for the convent of San Francisco.

The acclaimed paintings helped Murillo rise to fame, bringing him a series of commissions and ensuring he had work.

Around the early 1650s, Murillo experienced a change of style, characterised by softer outlines, eventually veering towards a more vaporous effect.

The painter, who came from a financially humble family, married the wealthy Beatriz de Cabrera y Sotomayor in the 1640s.

He died on 3 April, 1682, around the age of 64.

Murillo’s paintings are full of soft lyricism and grace. His art attracts by the intimacy of mood, sincerity and warmth of feeling.

Like all Spanish artists of his time, Murillo painted mostly on religious themes. But this did not prevent him from showing truthfully the life of common Spanish people. His Madonnas were copied from ordinary Seville women; many religious scenes are depicted by him as scenes from everyday life. He often found his heroes on the streets of his native town.

Murillo was famous among contemporaries for his benevolence. And his canvases are full of magnanimity. In the Letters on Spain, art historian V. Botkin, writes about Murillo’s painting: “In the airy brightness of light, in the transparent darkness of the shadows of Murillo, some kind of transformed poetic life breathes. Add to this special, belonging to him alone, the uncertainty of the contours that merge with the air. All this creates inexpressible unearthly harmony.”

The Virgin of the Rosary, 1650

The painting conveys one of Murillo’s favourite themes, the Virgin and the Child. The virgin is in a vibrant red dress, she sits on a deep blue shawl and holds the child, who sits on her lap. The two figures tenderly сling to each other, as only a mother and a child can do, which is a typical element of Murillo’s paintings. This tender touch is indicative of a realistic element that is present in all of Murillo’s paintings.

Immaculate Conception of Soult, 1678

The Immaculate Conception was one of the themes that brought Murillo great success. The image shows the Virgin Mary, surrounded by a fleet of angels, floating upon the clouds. Although many of his paintings depicted a strong version of reality, this painting soars in imagination. The Virgin is clothed in light, the halo shining around her head. The angels, drifting in a playful manner near her, look upon the Madonna with admiration. Some try to touch her tenderly, as if she is their beloved mother.

Two Women at a Window, 1655-1660.

The triumph of life is joyously affirmed in his beautiful painting Two Women at a Window. In this amazingly lifelike scene, Murillo uses the technique which helps him to break the frame between art and life. A young woman rests her elbows on a windowsill, smiling. The effect is dramatically three-dimensional and real. She seems to come forward, into our space. This masterpiece of everyday life puts us straight onto the streets of Seville.

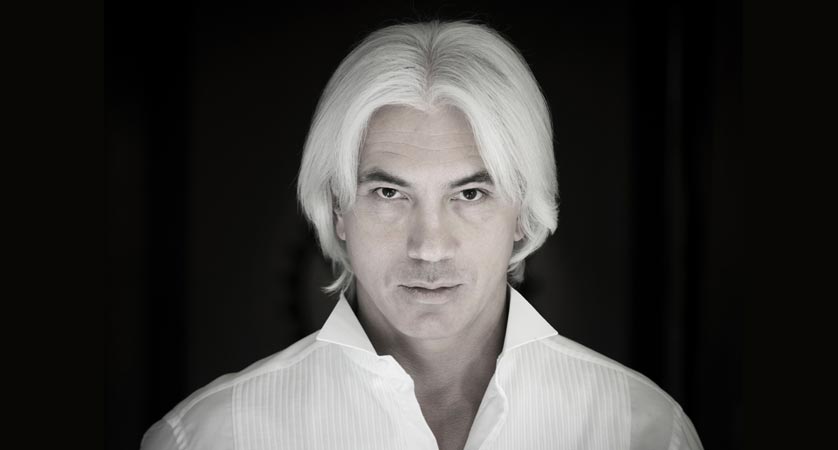

Self-portraits, 1650-55, 1670

When Murillo was in his 30s he imagined what he might look like if his forgotten tomb was discovered hundreds of years after his death.

In the first of his two surviving self-portraits (1650–55), Murillo gazes out from an oval picture that is held within a mouldering grey stone slab. This piece of timeworn rock rests at an angle, as an old monument dug out of a crowded graveyard might lean against the cemetery wall.

Twenty years later, Murillo portrayed himself again; getting older and closer to the tomb he decided once again to enclose his image in stone. Yet he seems more confident now. If the earlier picture showed him as a forgotten fragment, his image in this painting rests on a shelf where the signs of his art – a drawing, dividers, a ruler, a paint-smeared palette and brushes – are proudly displayed. In a subtle but brilliantly effective assertion of the life-giving power of art, Murillo puts his hand on the stone frame so that it seems to emerge into the real world. Colour triumphs over greyness, as bright pigments shine from his palette.

“Boy with a dog”, 1650

The boy is depicted with great love. A cheerful good-natured look, a joyful smile make him amazingly beautiful. Warm light seems to radiate from the boy’s face. The image is unforgettable.