His dance pictures sing:Edgar Degas

Degas was as obsessed with dancers and capturing the way they moved as Monet was with capturing the light through the day on haystacks, buildings and his garden.

They were not similar as artists. Most of the impressionist group – whose exhibitions Degas showed in from their beginning in 1874 to their last in 1882 – were concerned with colour and the play of light on landscape and the life of the new world they championed. Degas, who was also concerned with capturing the life of the new world, did so in a far more studied way, interested at first less in colour than form and technical experiment. The “enplein air” painting so beloved by most of his colleagues he openly derided, nor was he much taken by the efforts of his fellow impressionists to achieve effect through the spontaneity of brushwork directly on canvas. And then there was the question of personality. Most of the Impressionists felt themselves part of a group pioneering modernity in good spirits. Degas was a loner with an acerbic wit and a habit of losing friends. “All his friends had to leave him,” commented Jean Renoir. “I was one of the last to go, but even I couldn’t stay till the end.”

Degas was on the right side of art. His radical approach to technique, his efforts – through painting, print, photography and sculpture – to pursue his chosen themes, his startling compositions and, above all perhaps, his pastels and work in oil on paper earned him far greater influence on his successors and on modern art than any of his colleagues in the movement.

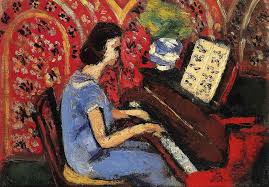

Nowhere more so than in his paintings of ballerinas, a theme he pursued throughout his long working life: drawing, modelling, photographing and painting them in almost every gesture and movement from the early 1870s until the time he ceased working in the first decade of the 20th century.

Why this obsession with the dance in general and the ballerinas in particular? He himself always evaded a clear answer, talking at one time of the classical tradition going back to Greece, at other times of its suitability as a subject of drawing. “They call me the painter of dancers,” AmbroiseVollard, the art dealer, later recalled him as saying, jokingly. “They don’t understand that for me the dancer was a pretext for painting pretty fabrics and rendering movement.”

Capturing motion certainly challenged Degas in a peculiarly obsessive way. All his career he sought to present the human figure, not in repose or monumentality, but in action or preparation for it.

Going backstage at the Paris Opera and hiring dancers to hold poses in his studio, he made endless studies in his sketchbook of their actions and dress.

Starting with a preliminary sketch of the central figure of his composition, he would then expand it with added drawn sheets until he had the full picture prepared, which he then transferred by canvas, often using the grid system used by the Italian fresco artists of the Renaissance, whose work he spent two years copying as a young man. Once worked up, he would then keep retouching and making slight changes until the canvas was taken from him.

It was the same with pastels and his painting in thinned oils on paper (“essence” as it was called). The paint or pastel lines were looser, the colours bolder, particularly as his eyesight started fading in his seventies and oil on canvas became more laborious. But the preparation was as exacting and his effort to build up colour and texture by fixing one layer and then adding another was an invention of his own, as was his development of monotype engravings, in which he painted directly on to the plate and then soaked a paper upon it. He used them not just to experiment with composition but also as the foundation on which he could then add pastel or oil.

He also wanted, in his dance picturesto delineate the female figure with scientific accuracy.He astounded the art world in the 1881 Impressionist Exhibition by showing the now-famous wax sculpture Little Dancer of Fourteen Years, with real hair, dress and ballet pumps.

His early rehearsal paintings are still quite formal in their composition, the dancers painted in groups arranged against windows and staircases.

Like all the Impressionists, he was profoundly influenced by the Japanese woodblock prints becoming available at the time, with their use of bold, block colours, their fresh angles of vision and their drastically cropped figures. They also taught him to be unafraid of using large empty spaces in his compositions. His early pictures of the rehearsal rooms are masterpieces of line and space.

As his work developed, however, so did his concentration on the dancers themselves and the flow of their limbs and costumes. It was the performance itself he wanted to capture, with quite startling viewpoints and close-ups, bringing not just movement to life but making the viewer into the audience.

Partly influenced by young painters such as Gauguin and Van Gogh (whose work he bought surprisingly early) he went for the sense of vivacity and swirl in his dancers, framing them in small groups of two and three as if they were one and the same person in different poses: in blues and oranges and yellows of vivid freshness.

Degas is the artist’s artist of the Impressionists; the man younger painters looked to for ideas and novel experiment. With Monet and Renoir, you don’t need X-rays of the canvas to understand what they were up to. Their approach was relatively simple, if the effect was complex. But with Degas, examination of the works does throw new light on how he achieved what he did.

Knowledge of his working methods does deepen your understanding and increase your respect for his work.

The most amazing thing about his dance pictures is that they sing.