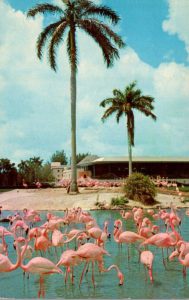

The long-awaited return of the elegant bright pink American flamingo to Florida

The bright pink American flamingo, the amazingly beautiful wading bird, rivals only the Roseate spoonbill for its exuberant plumage.

While flamingos were once common in the Sunshine State — giving rise to the references in lawn décor, literature, art and business names — the growth of the plume hunting industry in the 1800s, followed by the draining of the Everglades in the 20th century, decimated Florida’s flamingo population. As flamingos faded from the landscape, so did many of the other wading birds that rely on shallow water for their meal.

For the next century, American flamingos were only spotted in remote islands off Cuba, throughout the Caribbean and near Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

In recent years, a few of the unmistakable birds were spotted in South Florida and the Keys, as well as the Florida panhandle. But when Hurricane Idalia churned through the Gulf of Mexico in August 2023, researchers believe the storm’s winds diverted some flamingos from their typical flight patterns through the Caribbean and steered them north. In September 2023, birdwatchers across the country began posting flamingo photos as far north as Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

Four flamingos were spotted by Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge during December 2023. Photographer Thomas Lynch captured the image, which allows to compare the size of the flamingos with the white pelicans and brown pelicans.

Still, most were found in Florida, with nearly 70% of the flamingos observed in the Florida Keys and in Florida Bay, which is part of Everglades National Park, said Jerry Lorenz, Audubon Florida’s director of research.

From Feb. 18-25, 2024, Audubon Florida organized an American Flamingo survey, in which 40 people participated. They reported seeing 101 wild flamingos, and survey organizers made their best effort to eliminate duplicate sightings. Audubon Florida released the results of the survey May 6.

The flamingos were reported in three main locations: 50+ were spotted in Florida Bay; 18 were counted in the Pine Island area; 14 were reported at Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge.

The flamingos have continued to be spotted in 2025. The two consistent areas are at Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge and in Estero Bay near Fort Myers Beach.

Flamingo sightings have been recorded in Florida since the 1950s. Of real birds, not the ones floating in your neighbor’s pool.

But for decades, the enduring question was where did they come from?

Were these birds actually native to Florida or merely transients from nearby Caribbean colonies? After all, American flamingos are found across the Caribbean, to the Yucatan peninsula and northern South America, predominantly in mud flats, inland lakes and lagoons in estuarine or coastal areas. They can disperse long-distances, so perhaps they were just another visitor come to enjoy Florida’s sunshine and endless beaches. Or maybe they hadn’t traveled at all.

For a long time, sightings of flamingos were dismissed as escapees from captive populations, especially the one in Hialeah.

In 1931, Joseph Widener, a wealthy Philadelphian art collector, had just purchased the Hialeah racetrack. He imported 20 to 30 flamingos from Cuba for the grounds. They promptly flew away the next day. Undaunted, he imported more, and this time they stayed.

Charming the public with their good looks, not long after the Florida Derby was renamed the Flamingo Stakes. Winston Churchill is alleged to have painted their portrait while visiting Miami in the 40s. Miami Vice and several movies captured the flock on screen, and the charismatic flamingo was cast on the Florida lottery ticket. The flock remains today, and it was long believed that its famous individuals were the source of the mysterious flamingo sightings.

How did flamingos get here?

This question came to head in 2015 when a juvenile flamingo was discovered in Florida Bay. Flamingos are born white and only turn pink from eating shrimp, so the juvenile flamingos are not-so-pink birds. Hoping to find an answer once and for all, a group of researchers working at Zoo Miami and Audubon painstakingly captured him, attached a satellite tracker to his leg, and affectionately named him Conchy. They released him and waited, eagerly, to see where he would fly: Cuba, the Bahamas or Mexico? Instead, in classic teenager style, Conchy refused any of the above, and stayed in Florida Bay. One more piece was added to the puzzle. Determined, the researchers set out to solve the mystery, and their results came out in summer 2018 to much acclaim: flamingos are Floridian after all.

Flocks of American flamingos were once abundant in Florida and the Florida Keys. Before 1900, observations of flocks in the thousands were recorded in field notes and journals. Fragile pieces of paper miraculously surviving the test of time to be digitized and discovered by a team of scientists. But not all sightings were innocuous, some of these birdwatchers were also plume hunters. The flamingo’s beautiful feathers were sought to embellish women’s hats, and they were also hunted for food. In one account, more than one hundred flamingos were killed in a day. They followed the fate of many other eye-catching birds in Florida, massive declines. By the turn of the century, they were no longer found in Florida.

Another important clarification for flamingo’s status is whether they actually bred here in Florida. Here the evidence is scant, but among jars of preserved snakes, shelves of skulls and drawers of stuffed songbirds, researchers could find a refreshing sign of life, eggs. Flamingo eggs to be exact, preserved since the late 1800s in Natural History and Vertebrate Zoology Museums. Scrawled across cards or their fragile shells is another clue, Florida, their origin.

So that brought researchers back to the original question, where are our feathered friends coming from in recent times? Given the popularity of the Hialeah racetrack flock, it was a plausible explanation that flamingos came from there. But turns out, there’s no evidence for flamingos flying away from their home, especially one that has a stable food source.

And in 2015, a flock of 147 flamingos appeared in Palm Beach County. Such a large flock is unlikely to have escaped, all at once, from the smaller Hialeah population. Other captive populations do exist in Florida, but most birds there are tagged and wing-clipped to prevent escape.

The researchers returned to the idea of their Caribbean cousins. Here was more evidence, flamingos banded in the Yucatan peninsula have flown to Florida, as well as Louisiana, Cuba, Texas, and the Cayman Islands. Another species, the Greater Flamingo, tagged in beautiful countryside of southern France, have dispersed to Spain, Russia, and even Iran.

So, the majority of evidence points to the fact that we have guests and let’s hope they stay.

But is that the end of story? Even though populations in the Caribbean are stable or increasing, flamingos still face threats ahead. A major one is habitat loss, of 30 to 40 nesting sites that dotted the Caribbean before 1900, only 5 to 6 remain. Hurricanes can also cause major damage to nesting colonies.

For instance, Hurricane Irma killed thousands of flamingos in Cuba in 2017. The more intense tropical storms predicted under climate change may not be good news for flamingos. Other impacts from climate change, including sea level rise and pollution may pose an increasing threat to flamingos and their nesting grounds in the coming decades.

Dances and Flamingos

The flamingo’s name, derived from Spanish and Portuguese, has its origin in the word flame, just like flamboyant, appropriate for such a showy species. If you’ve ever embarrassingly referred to a Spanish dance as flamingo, you’re actually pretty close. The Spanish word, flamenco, refers to both the bird and the dance, both hailing from southern Spain. The Greater Flamingo, one of six flamingo species, is found in southern Europe. Why the two are associated together is a bit of a mystery.

Perhaps the dance was inspired by the elegant movements of the flamingo? Or the brightly colored flamenco dancers resembled their avian counterparts? At the moment, this is one question that remains unsolved.

By Gilbert Castro | ENC News