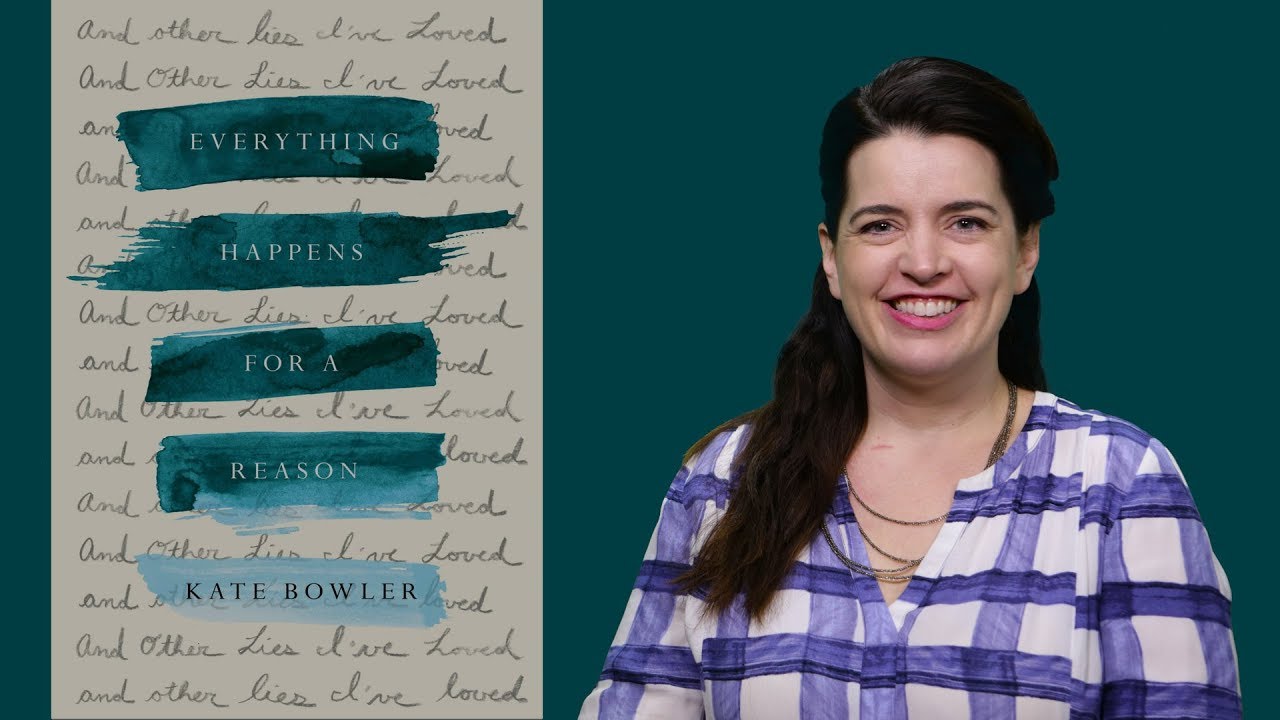

What Not To Say To The Terminally Ill: ‘Everything Happens For A Reason’

Kate Bowler’s new memoir, Everything Happens for a Reason And Other Lies I’ve Loved, is a funny, intimate portrait of living in that nether space between life and death. In it, she shares her experiences with incurable stage 4 cancer and gives advice on what not to say to those who are terminally ill.

She writes that sometimes silence is the best response: “The truth is that no one knows what to say. It’s awkward. Pain is awkward. Tragedy is awkward. People’s weird, suffering bodies are awkward. But take the advice of one man, who wrote to me with his policy: Show up and shut up.”

Why did you write Everything Happens For A Reason?

Bowler: When I was 35, suddenly I get this stage 4 cancer diagnosis, and it’s just like a bomb went off and everything around me is debris. And I’m thinking, “Oh my gosh, did I actually maybe expect that everything was going to work out for me?” And so I wrote the book more like a theological excavation project, like I was just trying to get down to the studs of what I really expected from my life. And I think I was a lot more sure than I realized … maybe that I was the architect of my own life, that I could overcome anything with a little pluck and determination.

The cancer diagnosis changed your outlook on life?

Bowler: Of course, it did. I kind of pictured my life like it was this life enhancement project, and like my life is like a bucket and I’m supposed to put all the things in the bucket. And the whole purpose is to figure out how to have as many good things coexisting at the same time. And then when everything falls apart, you totally have to switch imagination, like maybe instead, life is just vine to vine. And you’re like grabbing onto something, and you’re just hoping for dear life it doesn’t break.

How did that diagnosis affect your relationship to friends and family?

Bowler: I went from feeling like a normal person to all of a sudden, like this spaghetti bowl of cancer. I was trying to learn how to give up really quickly, like looking at my beautiful husband and just immediately all the stuff you’re supposed to say, which is just like, “I have loved you forever,” and “All I want for you is love.”

… You have these impossible thoughts like, “You will live without me,” and “Please take care of our kid.” And like you’re trying to do all that hard work and then in the same moment, they’re trying to rush in and say, “We’re going to fight this.” There’s all these plans they want to pour their certainty in, to remake the foundation. And there’s this, kind of, almost terrible exchange, where you’re trying to remake the world as it was. But it’s all come apart.

In the book you write youhad conversations with your 4-year-old son about death.

Bowler:You see, he is entirely impervious to all of this, in the best way. But I do think the thing that has radically changed is I really was, before, trying to create this little bubble around him and us, ’cause I thought, like, “It’s my job to protect you,” and then I realized that I would be the worst thing that happened to him if this went badly.

So then I thought like, “OK, parenting strategy change.” And I thought, ‘Well, if I can just teach you that there is still beauty in others in the midst of pain, then like, that’s my job.” So we work a lot on like, “How are you feeling?” like, “I feel frustrated.” And then getting him to notice the feelings of others.

How did you manage to cope with negative news about your diagnosis?

Bowler:Well I have rules for when things are too sad, ’cause sometimes, just the reality of things really feels like an avalanche, and it’s just going to sweep everything away. So I do make rules for the day, like don’t talk about sad things after 9 p.m., so I try to make my day a little gentler. I try to make other people’s day a little gentler. The other thing I do is I try really stupid stuff, like I got terrible news a couple months ago, which thankfully turned out to be a medical error.

It was a scan and it looked brutal, but I spent that week thinking like, “This is my last year for sure.” And it was weird because the next day, I turned to a friend and I said, “Would you like to go visit the world’s largest Ukrainian sausage?” And he was like, “Oh, I’m in.”

On your list of things not to say to someone with terminal cancer are: “How are the treatments going and how are you really?”

Bowler:This is the toughest one of all. I can hear you trying to be in my world and be on my side. But picture the worst thing that’s ever happened to you. Got it? Now try to put it in a sentence. Now say it aloud 50 times a day. Does your head hurt? Do you feel sad? Me too. So let’s just see if I want to talk about it today, because sometimes I do and sometimes I want a hug and a recap of American Ninja Warrior.