What Our Monuments (Don’t) Teach Us About Remembering The Past

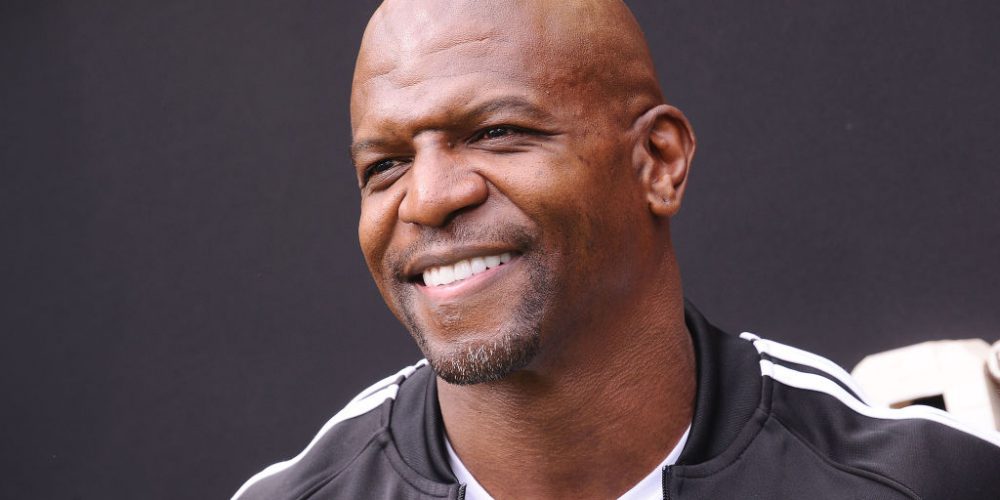

As the debate rages over what role Confederate monuments do — and should — play in commemorating U.S. history, Jennifer Allen says we can learn a lot from Germany.

Allen is an assistant professor of German history at Yale University, and she specializes in something called memory politics.

She also attended the University of Virginia, located in Charlottesville, where violent clashes earlier this month over a statue of Robert E. Lee brought this debate back into the national spotlight.

You were a student at the University of Virginia. What were your feelings about the Robert E. Lee monument in Charlottesville back then?

Allen: I’m embarrassed to admit this: I lived just down the street from the Robert E. Lee memorial and I must have walked past it dozens of times and never gave it a moment of thought. Incidentally, not four blocks away from that, there is another monument — even more inconspicuous in Charlottesville’s court square. A small plaque, embedded in the ground, that marks the site of a former slave auction. And I also walked past that countless times and did not pay attention to it at all.

Monuments don’t mean things on their own. They mean things because we make them mean things. So this Robert E. Lee statue, which I suspect most Charlottesvillians would have walked past and ignored as well, has taken on a new valence. And I think that’s an important reminder. Monuments are not static things that have a single narrative behind them. Monuments are things that we create. Monuments are objects whose meaning and significance we create daily.

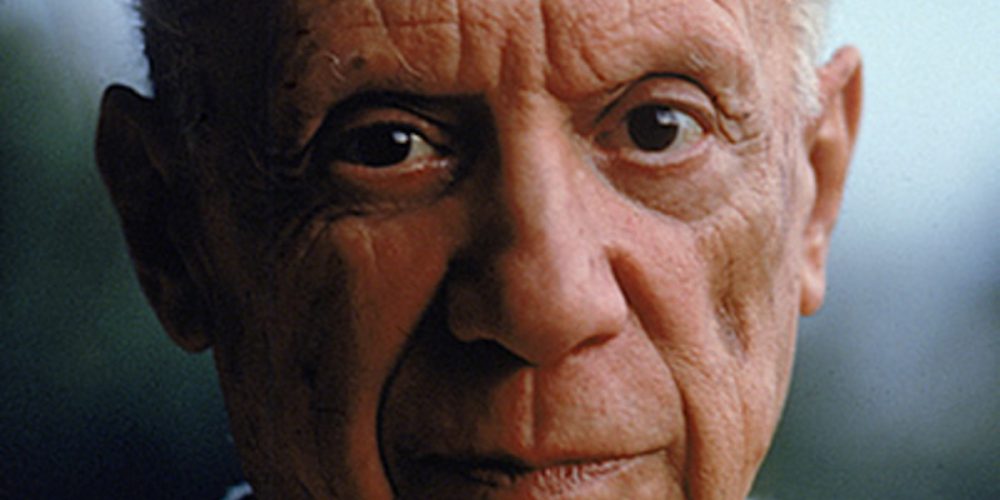

In the wake of Charlottesville, a lot of comparisons have been made between the way the United States commemorates slavery and the way Germany commemorates the Holocaust. So how has Germany dealt with its role in the Holocaust?

Allen: I think Germany is a really fascinating case study in the depths of human depravity and also the resilience of the human spirit.

The German case is interesting, and complex, and it has gone through many transformations. The Nuremberg trials are sort of the first important moment of reckoning, but also a complicated one. Part of what the trials did was identify a very select group of perpetrators. So it allowed one to say, “They were the ones who did this. Not me.”

The first big transition that you see in West Germany’s attempt to reckon with the legacy of the Holocaust was in the ’60s, with the so-called “generation of ’68,” who revolted against their parents. Who said “no, you’ve been too silent.” That’s a kind of second generation of reckoning. Those are the children of the perpetrators of the Holocaust.

And now you’re getting into a generation of grandchildren and of great-grandchildren, and I think that moment is where you start to see a sort of qualitative re-evaluation of the kind of forms memory and commemoration might take.

What can that teach us about reckoning with the history of slavery in the United States?

Allen: I think what we’re looking at right now is a kind of belated — one might say very belated — attempt to think through, yet again, what monuments to the Confederacy mean. How the United States wants to commemorate black history, African-American history, because really that’s what this comes back to, in the kind of “post-Ferguson” moment.

Memory is not just the things that we recall on a moment-to-moment basis. Memory is something that also means something in the world; what we decide is important to remember is something that is collectively determined, and the politics, the negotiation, the conversation by which we determine what matters and what doesn’t. Politics is a process of negotiation. So is the conversation over what should be memorialized, what should go in a museum, what should take the form of a monument, what should be a holiday.

All of these things we sometimes take for granted. We take for granted that we celebrate the Fourth of July. But what we’re seeing right now unfolding in the wake of Charlottesville is that, for example, commemorating the Confederacy is not something we should take for granted. It is something that is, in fact, debatable.

You mentioned that large grass-roots movement in Germany to commemorate victims of the Holocaust, often driven in part by the descendants of perpetrators of the Holocaust. Why isn’t there the same momentum in the United States to commemorate enslaved people?

Allen: The banal answer is that race relations are still very complicated in the United States. And the question of responsibility for commemorating the human aspects of slavery — that is, slavery not as an institution. To commemorate the Confederacy is to think, at most, abstractly about the way that slavery tied into that heritage. And I think with each successive generation, it has become more and more difficult to reckon with the question of responsibility. You see this play out in the debates about reparations.

In the German context, the Germans jumped immediately to make reparations to the Jews, to Israel, to other victims of the Holocaust. And we just never had that conversation. The further away you get, I think, there’s a sense of distance. “I didn’t own slaves. My parents didn’t own slaves. My grandparents didn’t own slaves. So why is this my responsibility?” Or, “I am an open, tolerant person. Why should I carry that burden?”

And I think that conversation is changing, too, as people — particularly the white American population — think about privilege in new ways. I think as people re-evaluate what their relationship is to people who carry the institution of slavery in a different way, namely black Americans, I think conversations about how to commemorate that event, as a human event, also change.