Trees are like people: they socialize and help their neighbours

Trees are social beings

Despite appearances, trees are social beings. For a start, they talk to each other. They’re also sensing, co-operating and collaborating, even across species boundaries. Peter Wohlleben, the German forester-turned-tree-whisperer and author of The Hidden Life of Trees, also says they are suckling their young, that juveniles are learning, and that some elders are sacrificing themselves for the sake of the next generation.

While Wohlleben’s view is a step too far towards anthropomorphism for some scientists, the traditional view of trees as isolated, non-sensory beings has been shifting for some time.

For example, the phenomenon known as “crown shyness”, in which similarly-sized trees of the same species appear to be respecting each other’s space was recognised almost a century ago. Sometimes, instead of interlacing and jostling for light, the branches of immediate neighbours stop short of one another, leaving a polite gap. There’s still no consensus on how this is managed – abrasion of growing branch tips is one possibility, another is that growth is inhibited when leaves sense infrared light scattered by other leaves close by.

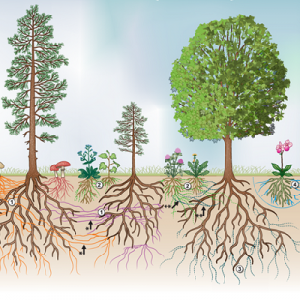

If trees can be shy at their branch-tips, more recent research shows they are anything but at their roots. In a forest, the hair-like tips of individual root systems not only overlap, but can interconnect, sometimes directly via natural grafts, but also extensively via networks of underground fungal threads, or mycorrhizae. Through these connections, trees can share water, sugars and other nutrients, and pass chemical and electrical messages to one another. In addition to serving in communications, the fungi extract nutrients from the soil and convert them into forms that trees can use. In return they receive sugar – as much as 30% of the carbohydrate produced by photosynthesis in a woodland goes to pay for mycorrhizal services.

“Mother trees”

Much of the current research on this so-called “wood wide web” stems from the work of the Canadian biologist Suzanne Simard. Simard describes the largest individual trees in a forest as hubs or “mother trees”.

“Mothers” have the deepest, most extensive roots, and are able to supplement smaller trees with water and nutrients, allowing saplings to thrive even in heavy shade.

Further experiments suggest that individuals are able to recognise close relatives and favour them when it comes to transferring the good stuff. Thus healthy individuals can support damaged neighbours, even leafless stumps, keeping them alive for years, decades, even centuries. This connectivity and collaboration makes much more sense when you realize that the dependent trees may not be random strangers, but old friends, or more persuasive still, close relatives.