Image of economy as of bucket full of money

What do people think the economy is? How do they think it works? How do you think it works, if you think it works at all? The New Economics Foundation, in its report, Framing the Economy, conducted 40 in-depth interviews in London, Newport, Glasgow, Wolverhampton and Hull, with the aim of finding points of common understanding. Though 40 is a relatively small number, the researchers were looking for images, metaphors, certainties and black holes that came up again and again, across regions and demographics.

From these tropes, they’ve been able to plot how, from 2010, the coalition government’s austerity agenda played so well into people’s hopes and fears; how the public attachment to it was so tenacious. How, even as the policy was failing to stimulate the economy in the way that had been promised, it was still seemingly resistant to counter-argument. Even once it was plainly, across the country, having devastating impacts on people’s lived experience (disabled people having their benefits removed and dying weeks later, the victims of the universal credit experiment evicted from their homes), the notion itself – that we all had to tighten our belts, and that was the responsible thing to do – was curiously buoyant, researchers note.

If anything, the more hardship it caused, the more necessary it was for many to cling to the narrative. And this was all underpinned by deeply held notions about how things “work”, researchers mention. The economy was seen as a container, the most frequent metaphor was a bucket: some people put in, and others took out. It was also seen as cash, almost exclusively, with other frames – productivity, investment – rarely getting a look in. By the bucket definition, the economy was finite, and economic disasters were the result of too many people taking out, and not enough people putting in, researchers state.

Obviously, one could give this a leftwing spin, and say the people not putting enough in were the tax avoiders, and the people taking too much out were rapacious corporates. But intuitively the people know that any discussion centred on this rusty and not-large-enough container will hold the economically unproductive as the drain; a nation divided into those who give and those who take may occasionally turn its ire upon the rich – but that won’t abate its fury against the poor, the researchers say.

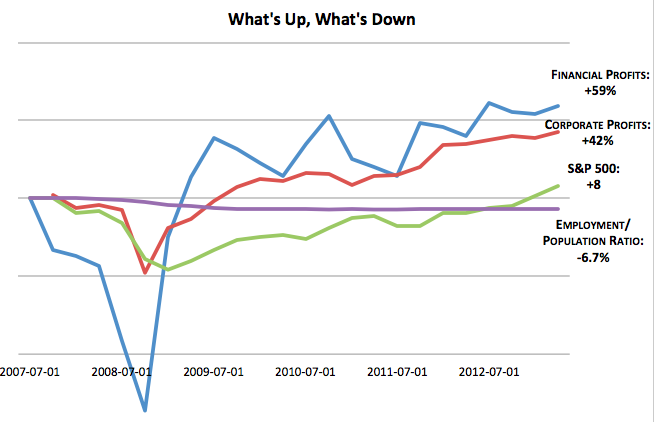

Not unreasonably, given the financial crash and its worldwide consequences, the economy was seen as intensely volatile, susceptible to grand forces whose actual nature fell into a cognitive black hole: “market forces” were seen as determining but utterly mysterious. Words like “falling” and “tumbling” were ubiquitous. The language was of natural disaster, and it was highly unusual to link this back to any human responsibility, except that you shouldn’t take too much out of the bucket. This may explain the paradox that, while inequality is seen as a bad thing, there was very little support for redistributive policies; asymmetry may be destructive, yet, like a weather event, it was beyond the wit of man to correct, the researchers continue.

Dora Meade, the lead researcher, was shocked by the “ubiquity and level of fatalism”. If you combine the feeling that the economy is something beyond a normal person’s understanding or control, with the sense that the system is rigged, “people are left feeling there is very little they can do. There’s no role for the general public, even if they believe it’s broken and unfair,” she says.

Perhaps the most dispiriting element is that, when asked to describe or imagine a functional, healthy economy, people turned always to an idealised past, when wages were high, inequality was low and we were more “self-reliant”. The resonance here is not with austerity, but with Brexit arguments: people weren’t necessarily blaming immigration for low wages; but they were imagining a past in which wages were higher, and linking that nostalgia to an era of self-determination whose erosion can only, logically, have come from elsewhere, the researchers mention.

The report goes on to describe the economic frames and images that might make people feel differently, less impotent, more optimistic: yet before we can talk about the economy as an ecosystem fostering meaning and fulfilment, rather than a bucket full of money, we need to have the courage, not of one’s convictions, but of one’s confusion.