The change we need starts with us. Douglas Barret, 400 North Creative

Doug Barrett is a photographer and videographer, internationally recognized, currently based in Manhattan, Kansas. He is owner of 400 North Creative.

Doug is a military veteran and former police officer. He speaks here about his experiences as an African American and his efforts to bring certain issues to light through photography.

Douglas, why are you so passionate about photography?

Douglas Barret: Well, I am a photographer because I believe that relationships foster a deliberate life. Relationships are the core of collaboration and intimate storytelling. Relationships create change.

My personal work documenting justice issues and marginalization in America is where I find these deep relationships and conversations.

I believe the camera is an overlooked sacred tool, which simultaneously holds humility yet also the power of a striking hammer when used properly.

For me, it is about powerful, long-form, visual storytelling. The documentation of history and the world for posterity and the educative process have been the main drivers for my work….

It is my belief, education leads to empathy, which is the first step in any change for good or justice.

So the idea of becoming a professional photographer was not something unexpected for you, was it?

Barret: Quite right. You see, I’ve taken pictures ever since my father gave me a camera for Christmas when I was 10.

I was that kid in high school who always had a video camera, and was always snapping pictures.

But I never really thought I could have a career in the arts. So, of course, I drifted off into careers that paid the bills and afforded me a way of life, and just due to life happening, I just decided, ‘You know what? Now’s a better time than ever to follow your passion and live through the eyes of the lens that I’ve always wanted to live through,’ and I did that, and here I am.

You’re a former police officer and a US military veteran?

Barret: Yes, I was a police officer in Gwinnett County, Ga. working in SWAT and narcotics. After my career in the police I joined the military and was stationed at Fort Riley. The injuries I sustained required three surgeries and led to a medical retirement. When I retired, I decided to stay here in Kansas.

How did you feel about Kansas after life in Atlanta?

Barret: Well, coming from Atlanta, everything about Manhattan was a culture shock.

But it put things into perspective. There’s a small-town feel where you’re able to learn your neighbor, have a community of folks, a different side to fast hustle and bustle of life.

One of my passion projects is called Yuma Street Manhattan.

I really love this small city and its people.

You often focus on social justice issues.

Barret: When you’re behind the camera and you’re trying to make your photographs, having an understanding of where you’ve come from being on the other side of the law, it gives perspective into what it’s like to be a black male, a black female or person of color living in America, dealing with these racial injustices that are going on.

Luckily I’m able to capture these moments peacefully in Kansas – and that’s what I’m trying to do.

Have you ever had any personal experiences with discrimination?

Barrett: Yes. Once I was falsely accused of stealing from a local store. Following the accusation, I decided to stick around and wait for the police to show up so I could plead my case, knowing full well that I was innocent.

In doing so, I was able to leave without further incident, but was also well aware of the discrimination I had just gone through.

For me, the police were not the issue. It, to me, was the hate, the upbringing, the personal motivations that this individual had against me. It’s the everyday life for us. It’s not anything special. This happens to millions and millions of black Americans every single day.

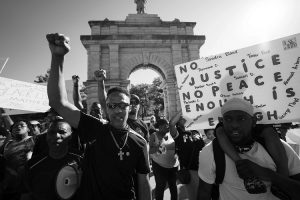

Your photos from protests in Manhattan after George Floyd’s murder brought you attention from the BBC, Fox News and Time and other national papers.

Barret: Well, their editors said they were apparently intrigued by images of Black Lives Matter protests all the way out in Kansas and asked me to share my story.

They said my photos powerfully captured the moment. TIME magazine featured a full page of my photo of a protester carrying a sign reading “Stop the Hate”.

‘Stop the Hate’ is a key message that will forever live, I believe.

Among the many collections on your website is your Homeless Veterans Project.

Barret: My master’s degree was in cyber-security and I was working as a remote senior project manager while doing photography on the side. My job allowed me to travel, and I began taking pictures of my fellow veterans I noticed on the street.

Since I started taking their pictures, I’ve made portraits of 75 veterans in 16 states. Each image is accompanied by a short description of the person and their circumstances.

What I’ve learned is these veterans are at such a vulnerable state they couldn’t even take an apartment if you gave it to them. Because they’re thinking, ‘Where’s my next meal?’ ‘How do I get myself clean?’ They can’t take a job because they don’t know how they’re going to bathe themselves or cut their hair or brush teeth to be presentable for a job.

After seeing your photos, people began to offer you money and other help to these suffering people?

Barret: Yes. People wanted to give me money. But I was just a photographer out documenting these stories.

And now, though, people can give money. Through the Greater Manhattan Community Foundation, I created a 501(c)(3) called Served Silent Homeless but not Hopeless.

On Veterans Day, donations are doubled through the U.S. Armed Forces Stand-to-Match Day.

Our organization has been across the country and has taken veterans food, coffee, hot cocoa, brought shoes for the shoeless, tents for those who needed shelter, boots for those in the winter, bus tickets for those trying to get to medical appointments.

Many of your photos are now in the permanent collection of the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art.

Barret: Last year I had a personal exhibition in this Museum.

It included 13 black-and-white photographs covering three different series: Manhattan’s Yuma Street neighborhood, Homeless Veterans across the country and the George Floyd protests in Kansas.

Any photographer, visual journalist, documentary photographer aspires to have their work in print at some point in a museum’s permanent collection.

Once you are afforded that opportunity, it’s a checkbox that’s completed, but your work will forever live, and the opportunity to have it at the Beach Museum of Art is a huge honor. It’s humbling.

I seek to communicate my message to the world through my photographs attempting to also make it a better place for my children so they don’t have to experience the same problems as me.

By Alex Arlander, Gilbert Castro | ENC News