He sowed the seeds of a new age: Jean-François Millet (1814 – 1875)

Jean-François Millet is an internationally recognized French painter of the 19th century.

An original artistic vision, unique manner of painting, unmatched style and color are the main distinguishing features of his work.

Best known for his paintings of peasants toiling in the countryside, Jean-François Millet was also a master of landscape and portrait. His works are filled with deep spiritual content. The artist saw virtue in righteous modest life, in physical labor on the land, in the unity of man and nature. He devoted his creative work to celebrating ‘nobility’ of ordinary peasants whose hard work and stoic life he greatly respected.

Jean Francois Millet was a co-founder of the Barbizon School of painters near Paris.

His art and personal convictions greatly influenced his successors. Impressionists, like Georges Seurat, admired his draughtsmanship and his depictions of light. Post-Impressionists, most notably Vincent van Gogh, were influenced by his subject matter, sculptural figures, and expressionistic brushwork. His work had an impact internationally upon Janos Thorma, Max Liebermann, Rosa Bonheur, and William Morris Hunt, among others. Salvador Dalí’s obsession with Millet’s The Angelus coincided with his own later religiously themed work.

Millet also had an inadvertent impact upon the laws affecting the art world. When The Angelus sold for a half million francs in 1889, fourteen years after Millet’s death, awareness of the dismal poverty of his family led to droit de suite laws that allow an artist’s heirs to receive part of later resale prices.

The Legacy of Jean-François Millet.

His art legacy is great. You can see here several of his most famous canvases.

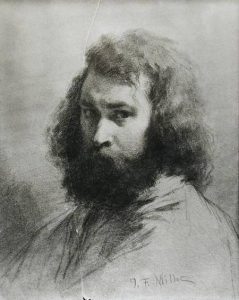

Self-portrait of Jean-François Millet (1845-46)

Charcoal and pencil on paper – Louvre, Paris

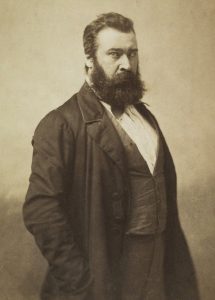

Portrait of Louis-Alexandre Marolles (1841)

While he was still in his twenties, Millet shared a small studio in Paris with his friend Louis-Alexandre Marolles. Perpetually short of funds, Marolles apparently persuaded Millet to make lighthearted pastels executed in the style of Boucher and Watteau, which they could sell for twenty francs each. Whether or not the scheme ever proved profitable, Millet’s portrait of his friend is skillfully drawn in an eighteenth-century Rococo manner. A drawing of a faun is barely discernible on an unfinished canvas in the background of this pastel.

Pastel on paper – Princeton University Art Museum

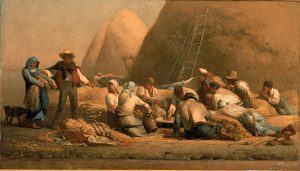

Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz) (1850-1853)

A group of harvesters, dirty and tired from their labors rest in front of large, golden-hued stacks of grain. On the left, a man presents a woman to the group.

Millet originally intended to depict the Biblical story of Ruth, a widow who met Boaz, the landowner and kinsman who eventually became her husband, while she was gleaning in the fields. Showing the work at the 1853 Salon, Millet changed the title to Harvesters Resting. One of his few works that show a group, rather than an isolated figure, in a landscape. It won a Second-Class medal at the Salon.

What has been emphasized is not the romantic Old Testament story of faith bringing two people together, but rather a contemporary group of hot and dusty field workers resting from their labors. Ruth’s face is downcast shyly, and Boaz, acting as intermediary, visually joining her figure with the group field workers. Thus, Millet brings into focus the common laborer’s centrality in history and scripture.

Oil on canvas – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Gleaners (1857)

Three peasant women gather grains from what’s left at the end of a harvest day as the evening shadows gather around them.

In Millet’s days, French farmers followed the Biblical injunction to leave gleanings (or left-over scraps of the grain harvest) in the fields so that poor women and children could live on them. Millet’s Gleaners occupy the extreme foreground of the canvas. The grinding poverty of the peasant women is evident in their rough, simple garments, and the back-breaking work of collecting individual grains. Shown at the 1857 Salon, the painting was criticized for its depiction of rural poverty.

The painting is dominated by the sculptural figures of the three women. The emphasized lines of their shoulders and backs convey the strain of the arduous work. Their faces are hidden, suggesting a sort of anonymity rather than individuality. The anonymity allows them to represent all the poverty-stricken peasants.

The contrast between the shadows lengthening around the women and the illuminated background where the harvesters are celebrating conveys the distinction between poverty and plenty. The distant steward on horseback, supervising the harvest, represents the privilege of distance from hard labor.

The viewer cannot help but realize how much effort the women must make to simply live. Even so, despite their straitened circumstances, Millet bestows a certain dignity upon them. They display a measure of quiet fortitude amidst the monotony of their efforts, and despite the simplicity of their garb, their figures are robust, accustomed to the rigors of their working life.

Oil on canvas – Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The Angelus (1857-1859)

Arguably Millet’s best-known work, The Angelus depicts a man and a woman standing in the foreground, with heads bowed, the man holds his hat in his hands, and the woman folds her hands in prayer.

In Roman Catholic villages of the time, the church bells would ring out three times daily, at 6 a.m., at noontime, and at 6 p.m. for the prayer (called the Angelus), and it is at such a moment that the couple stops their work to pray. Despite their humble circumstances, this simple act of devotion and the sculptural quality of their figures lends them a kind of quiet dignity, yet their worn clothes, and their bowed shoulders suggest a life of earthly toil. The gathering dusk engulfs them suggesting the difficulty and perhaps despair of their struggle. The Angelus, their prayer for deliverance, and the sky beyond still lit by the sun stands in stark contrast, punctuated by the steeple connecting Heaven and Earth.

Revisiting a subject that he depicted in The Potato Harvest of 1855, Millet painted this work as a commission for a Boston art collector. Originally called Prayer for the Potato Crop, Millet changed the title and added a church steeple. The work influenced Vincent van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters of 1885 and served as a catalyst for his return to painting, so great was his admiration.

For the artist Salvador Dalí, it became a kind of artistic obsession, recreating the scene many times in the 1930s. In his book The Tragic Myth of The Angelus of Millet, (1938) argued that the couple had actually been praying over their buried child. Dalí certainty may have been cemented by the words of the Angelus itself, which essentially condenses the Incarnation of Christ into three short prayers, one for each time of day, followed by the Hail Mary. The prayer for the evening is: ‘And the Word was made flesh: and dwelt among us.’ In 1963, in response to Dalí’s repeated assertions, the Louvre x-rayed the painting revealing an underlying geometric shape similar to that of a coffin in the place where the farmer was now digging potatoes.

Oil on canvas – Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The Man with the Hoe (1860-1862)

The Man with the Hoe depicts a fieldworker as he leans over, clearly exhausted from his labors, his hands upon his hoe. His clothes are rough and dirty, his face careworn, as he stares blankly into the distance.

At the 1862 Salon, both the public and critics reacted adversely to the work seeing the figure as a frightening, brutish giant and the painting itself as a social protest on behalf of peasants. Millet seemed to foresee the response to his work, when he wrote, “The Man with the Hoe will get me into hot water with a number of people who don’t like to be asked to contemplate a different world.”

The man is exhausted. His face, staring off into the distance suggests how mind-numbing such work is. The trench he is cutting leads into the distance toward the green field, the eventual reward. Millet wrote, “Is the work these men do the sort of futile labor that some folks would have us believe? To me at any rate it conveys the true dignity, the real poetry of the human race.”

Millet employs a number of strategies in his painting to convey his sympathetic message of dignity in the labors of man. His man occupies the greater portion of the foreground. And, although his posture bespeaks weariness, it creates, with the inclusion of the hoe upon which he leans, a pyramidal arrangement – a compositional element that implies stability, balance, and strength. The man looms higher in the picture plane, enhancing the viewer’s impression of his stature. The figure is surrounded by open space; no other objects compete with his presence so as not to diminish the perception of stature. The result is a sense of heroic strength and nobility in the pursuit of hard work.

Oil on canvas – J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

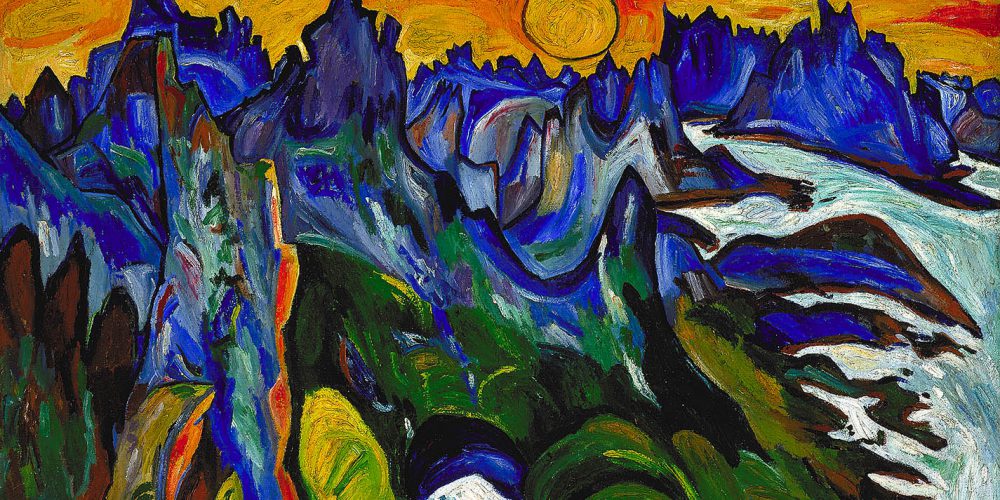

The Cliffs of Gréville (1871-1872)

Depicting the rugged beauty of the Normandy coast, the work shows the view of the ocean from the Gréville cliffs, their greenish brown slopes and the ocean breaking along the rocky shore lit by the sunlight of a hazy golden sky.

He painted this shorescape of the English Channel many times throughout his career. Unlike most of his works that focused on the laborer at work in the fields, this painting features the primal landscape itself.

The entire composition conveys a sense of underlying tension. The ceaseless back and forth motion of the waves batters a rocky shoreline and finally meets the far horizon. Yet, for all its sense of movement the asymmetrical segments are so perfectly balanced the composition is saved from devolving into chaos. Millet’s painterly style at this point includes loose, gestural brushwork very much in keeping with the Impressionist manner of Monet, and van Gogh’s works. The artist used graphite and ink to accentuate certain aspects of his landscape: the rocky shoreline, various planes of shadow on the boulders and the cliff-face, and high up at the horizon.

Oil on canvas – Albright-Knox Art Gallery Buffalo, NY

By the mid-1860s, Millet’s work was beginning to be in demand. Official recognition came in 1868, after nine major paintings had been shown in 1867 at the Paris Universal Exposition, and in 1868 Millet was awarded the Legion of Honor.

Important collections of Millet’s pictures are to be found in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and in the Louvre Paris.