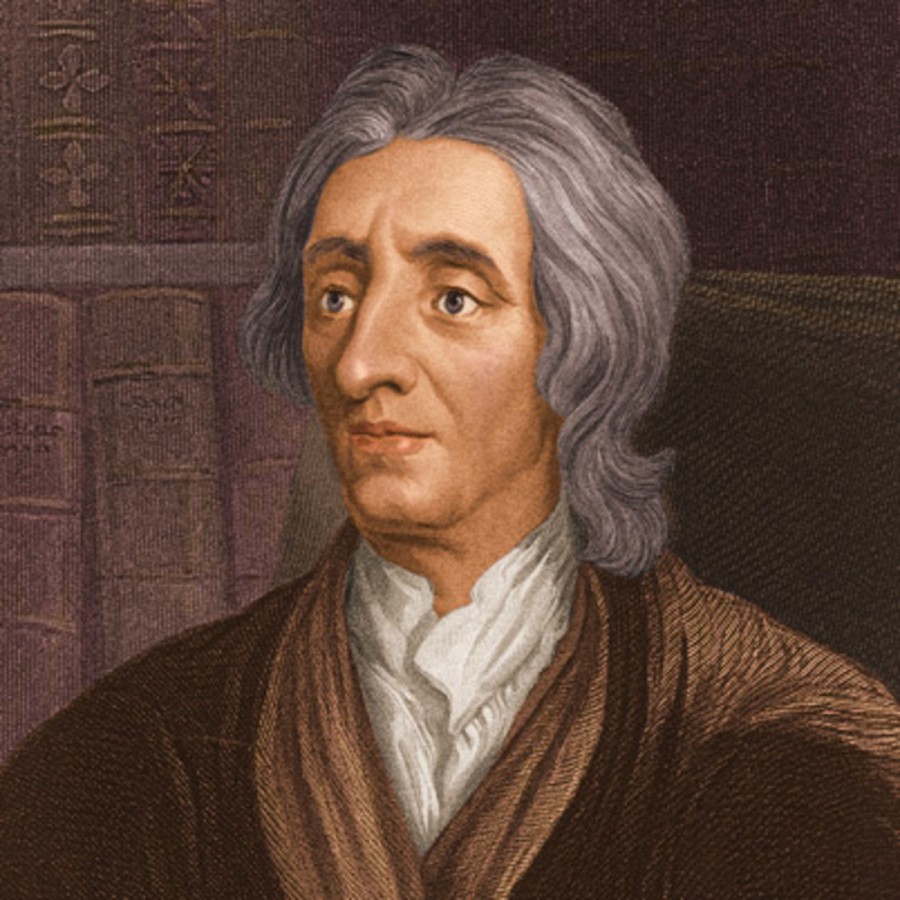

John Locke: The Man Who So Impressively Embodied the English Spirit

His celebrated essay, available to its first readers in December 1689, though formally dated 1690, is still of great interest today. It is an examination of the nature of the human mind, and its powers of understanding expressed in brilliant, lapidary prose: “General propositions are seldom mentioned in the huts of Indians: much less are they to be found in the thoughts of children.”

In the first two books, the argument moves through the source of ideas, the substance of experience (the origin of ideas), leading to a discussion of “the freedom of the will”: “No man’s knowledge here can go beyond his experience”. In book three, Locke proceeds to discuss language, and in book four he defines knowledge as our perception of the agreement or disagreement between ideas.

Eventually, after several arguments of great intricacy and subtlety, Locke establishes good arguments for empirical knowledge, and moves to explore the existence of God, discussing the relations between faith and reason: “Reason is natural revelation, whereby the eternal Father of light, and fountain of all knowledge, communicates to mankind that portion of truth which he has laid within the reach of their natural faculties.”

The Essay is a challenging read, made greatly more appealing by the elegance and comparative simplicity of Locke’s prose. The discourse eventually became a popular classic, and also a set text among university students. In 1700, when the young student George Berkeley, who would eventually reject so much of Locke’s thinking, entered Trinity College Dublin, it was among the prescribed texts. In 1700, the Essay was translated into French; a year later it was rendered in Latin, the supreme Age of Reason accolade.

Together, Locke and Newton would become English figureheads of the Enlightenment. With Newton, Locke did so much to sponsor the 18th-century picture of the world as a kind of celestial clock, a vast and mechanical assembly of matter in motion, with man taking his place as an element, like a cog, in a regular and predetermined universe.

Locke’s portrait of man as part of, not separate from, the rest of nature is also owed to the Essay. He had, of course, been anticipated in this by his predecessor Thomas Hobbes, but he went further. In the Essay he treats man as an appropriate subject for objective investigation. Thus, in his examination of human understanding, he follows a “plain, historical method” of careful observation, a method that would be adopted by later thinkers as various as Jefferson and Darwin.

It is hardly a surprise, therefore, that Locke should have had an important effect not merely on philosophy and psychology, but also on thought and literature. You can trace Locke’s influence, through the Essay, on the writing of Addison, the prose and poetry of Pope, the fiction of Laurence Sterne, especiallyTristramShandy, and perhaps above all in the writing of Dr Johnson’s great Dictionary of the English Language.

Bertrand Russel once said, possibly speaking for effect, that Locke had made a bigger difference to the intellectual climate of mankind than anyone since Aristotle. He added that “no one ever had Common Sense before John Locke” – and common sense was the watchword of much 18th and 19th century English endeavour. A sentence such as “I have always thought the actions of men the best interpreters of their thoughts” could equally have been written by Johnson.

“Nonetheless, there is really no writer who more impressively embodies the English spirit than Locke, in the sense that it is he who teaches us to think for ourselves, to weigh evidence empirically, to keep belief within limits, and to put all things to the test of reason and experience”, Robert McCrum says. “He is also witty”, continues he citing Locke’s well-known aphorism “All men are liable to error; and most men are, in many points, by passion or interest, under temptation to it.”

A signature sentence

“The commonwealth of learning is not at this time without master-builders, whose mighty designs, in advancing the sciences, will leave lasting monuments to the admiration of posterity …in an age that produces such masters as the great Huygenius and the incomparable Mr Newton… ’tis ambition enough to be employed as an under-labourer in clearing ground a little, and removing some of the rubbish that lies in the way of knowledge.”

(From An Essay concerning Human Understanding)