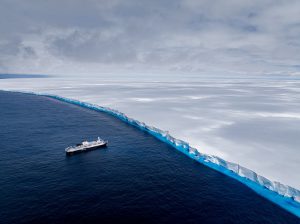

A23a, the world’s largest iceberg, is trapped in a vortex and rotates 15 degrees per day

If icebergs were humans, A23a would be a millennial. And like members of that generation who have sometimes been forced to stay home by harsh economic conditions, the iceberg has spent most of its independent existence grounded, stuck to a sandbank in shallow waters.

Little by little, the iceberg kept scouring a path over the seafloor and toward deeper water, nudged by currents, the wind and other factors. A breakthrough came in 2020, when the main bulk of A23a freed itself and started to pivot clockwise on its southeast corner. Before long, it was moving in earnest.

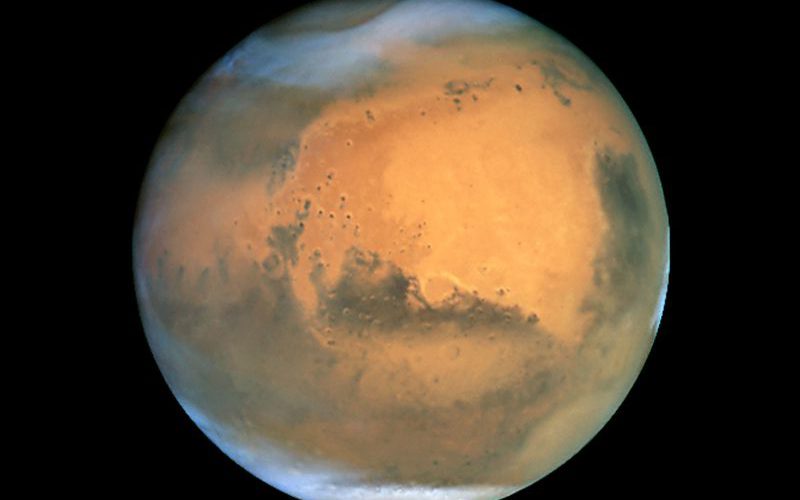

Iceberg A23a measures 40 by 32 nautical miles, according to the U.S. National Ice Center. For comparison, Hawaii’s island of Oahu is 44 miles long and 30 miles across. And New York City’s Manhattan Island is about 13.4 miles long and spans around 2.3 miles at its widest point.

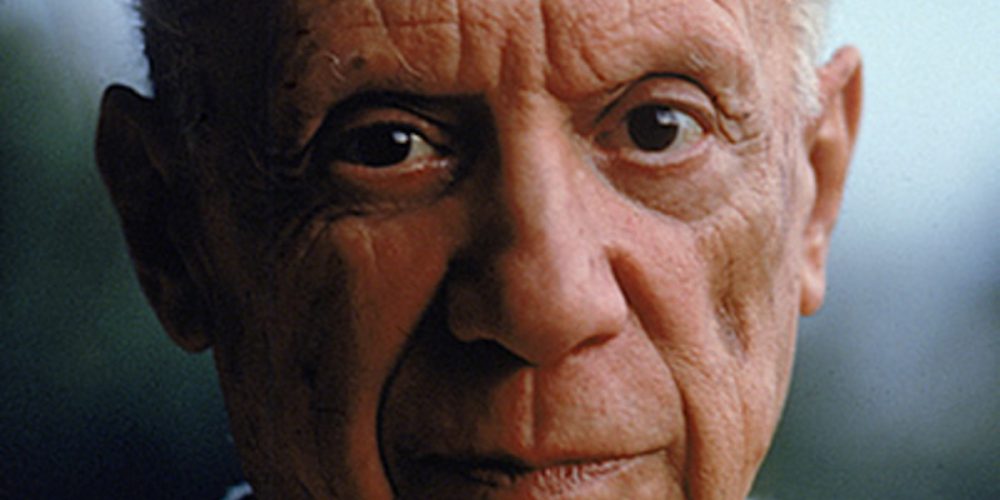

“It’s a trillion tons of ice. So it’s hard to comprehend just how big a patch of ice this is,” Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder said.

Ships plying the frigid waters near the Antarctic Peninsula, south of South America, will need to keep an eye on their radar for a floating island of ice: “The largest iceberg in the world, A-23a, is on the move into open ocean!” as the British Antarctic Survey recently announced.

A23a hasn’t always held the title. In 2021, for instance, it was supplanted by iceberg A-76, which broke from the Ronne Ice Shelf, also in the Weddell Sea. But that giant soon fractured into smaller icebergs, putting A23a back into the top spot.

“It’s truly a gargantuan piece of ice,” Scambos said, noting that the iceberg is likely 1,000 to 1,200 feet thick.

Its roots stretch to the austral winter of 1986, when the Filchner Ice Shelf’s leading edge broke off to calve three huge icebergs: A22, A23 and A24. In late 1991, A23a became a separate iceberg.

Life can get weird on an iceberg

If you were to set foot on A23a, Scambos said, you likely wouldn’t realize it’s an iceberg, floating loose at sea. Its scale would simply fill the horizon; any movement would be imperceptible. He should know. He has camped on icebergs before.

Scambos recalls one odd thing: the disorientation. “The ice that the base was built on would start to rotate, and that would make the sun do funny things in the sky,” Scambos said. “It wouldn’t be where it’s supposed to be in the morning or in the evening or at night — even though it’s 24 hours of daylight.”

Over the years, he has heard from people who want to visit an iceberg. And Scambos says that while some of their goals were outlandish (as in people hoping to declare unilateral sovereignty over an ice kingdom), a gigantic iceberg like A23a is pretty stable — with a big caveat.

“It’s not impossible to land on it,” Scambos said. “I mean, the upper surface is going to be smooth and snowy and relatively safe, at least for now.”

But as the iceberg drifts north and finds warmer conditions, melting and flooding will begin.

“Eventually it will start to crack apart fairly rapidly towards the end,” he said. “You wouldn’t want to be on it at the end, because the whole thing would be breaking off in pieces and falling into the ocean.”

Huge icebergs have drifted far distances

Most icebergs emerging from the Weddell Sea tend to drift slightly eastward toward South Georgia, an island in the sub-Antarctic region. some 1,000 miles east of the tip of South America. If that happens to A23a, it could run aground again near South Georgia.

This prompts inquiries and apprehensions about potential outcomes when a massive ice chunk nears land.

South Georgia is known for its diverse marine life and lots of seabirds. A big iceberg like A23a coming close could cause some disastrous changes. It can mess with ocean currents and disrupt the normal way things work in the sea. This might not be great news for the flora and fauna that call South Georgia home and can affect their livelihood in various ways.

But other icebergs, like its sibling A24, have moved more directly north, toward the Falkland Islands.

“Usually they’re in the process of breaking up at that point,” Scambos said, “although this one is likely to survive longer than most because it came from a colder part of Antarctica” and is thick, along with having a heavy buildup of snowfall.

If A23a doesn’t get hung up in shallow and warmer waters, he added, “it could wind up drifting south of Africa into the Indian Ocean. They’ve even drifted all the way into the Pacific and wound up coming up on Chile, almost circumnavigating the globe. Some of the largest icebergs have done that in the past.”

A few months into A23a’s journey, onlookers were stunned at what they saw: the iceberg spinning in circles.

Through satellite imagery, British Antarctic Survey noticed the mega iceberg rotating near the South Orkney Islands, about 375 miles from the Antarctic Peninsula, starting in January. According to the Survey, A32a maintains “a chill 15 degrees rotation per day.”

Its dance moves likely are caused by a phenomenon in fluid mechanics known as a Taylor Column. It’s essentially a rotating cylinder that forms when there’s an obstruction in a flow. In other words, A23a is trapped in a kind of ocean vortex.

Till Wagner, a professor in University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies how ice interacts with climate, said he has never seen a real-life example of this phenomenon on such a massive scale. “You know, you can make these Taylor Columns quite easily in a rotating tank experiment in your lab. But to see it on a geophysical scale like this is really rare” he said.

It’s unclear how long this ‘behemoth’ will spin in the vortex. The iceberg is also melting while spinning, and Wagner is curious to see how it will affect life in the surrounding ecosystem, like phytoplanktons. “It would be interesting to see whether next spring, we have like more active phytoplankton blooms in that spot,” he said.

“There’s a lot of life that lives in the bottom of the ocean that is just completely crushed, wrecked, when one of these things passes over,” Scambos said. “That’s it for the ecosystem that lives in that part of the ocean.”

“The main scientific source of interest for the iceberg is sampling ocean surface waters behind, near, and just ahead of it,” Em Newton of the British Antarctic Survey said of A23a. Researchers, she added, want “to understand the effects of temperature, changes to salinity, released nutrients, etc., along its path.”

This part of the Southern Ocean is normally very poor in nutrients. An iceberg like A23a, Scambos says, can help change that by shedding nutrients it accumulated from Antarctica and stirring up deep water, possibly sparking a plankton bloom in its wake.

What about climate change?

News of the iceberg’s peregrination comes after record warm temperatures and low levels of sea ice have been recorded around Antarctica in recent years. “In February 2023, sea ice around Antarctica reached the lowest extent ever observed since the start of the satellite record in 1979,” the NASA Earth Observatory said. And in September, researchers at the National Snow and Ice Data Center reported the lowest winter maximum extent of Antarctic sea ice. It was found to be nearly 400,000 square miles below the previous low, set in 1986.

“But despite several recent years of low extents, the long-term trend for sea ice in southern polar waters is essentially flat,” the NASA Earth Observatory said, adding, “it is the declines in sea ice at the other pole — in the Arctic — that are pushing the global sea ice trend downward.”

Scambos agrees, noting that A23a came from a part of Antarctica that is fairly stable. “These big icebergs are spectacular, but they’re just the way Antarctica works. This is how an ice sheet works. It gathers snow, and the snow thickens and flows off into the ocean, and then pieces break off. And in Antarctica, those pieces are really, really large,” he said.

“But the more important thing for people to be aware of is that Antarctica in other places is losing ice very rapidly,” Scambos said, describing a dynamic that contributes to rising sea levels.

“And that actually is a much more serious problem.”

By Alex Arlander | ENC News