Citizens in Atlanta saw art as a great refining influence upon people: Art in Atlanta at the period of its height (1930s – early 1940s)

The period of artistic development in Georgia from 1895 to 1960 reached its height during the Great Depression years of the 1930s and early 1940s.

The development of art was sparked by the influence of the art exhibition shown at the Cotton States and International Exposition in 1895, as well as by the establishment of museums early in the twentieth century.

Growing out of localized artistic efforts and traditions in Atlanta and Savannah, this watershed era also resulted from the emergence of the American Scene aesthetic, with its emphasis on regional subject matter.

In the years following World War II (1941-45), Georgia’s artists, both formally trained and self-taught, moved toward a more personal and intimate art expressed in the language of abstraction.

From 1895 through the 1920s

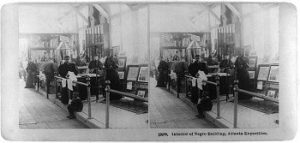

The art communities of Atlanta and Savannah flourished around the turn of the twentieth century. In Atlanta the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition, a sprawling fair held in Piedmont Park, featured a wide range of national and international art.

The establishment of the Emory University Museum (later the Michael C. Carlos Museum of Art) and the High Museum of Art, as well as an art school, further encouraged the growth of the arts in the city.

Meanwhile, the older artistic community in Savannah thrived with the expansion of the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences (later Telfair Museums) and the influx of trained artists into the city.

Atlanta

Although Atlanta was not considered an American art center at the time of the Cotton States exposition in 1895, Atlanta had hosted yearly Piedmont Expositions since 1887, as well as a number of highly publicized loan exhibitions.

The Cotton States exposition, however, essentially announced the city’s ambition to make the visual arts an important part of Atlanta culture and marked a turning point in the history of art in Georgia.

The display of approximately 1,000 paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures by Americans and Europeans was arranged by Horace Bradley, head of the fine arts department of the exposition, and exhibited in the city’s Fine Arts Building, a Greek revival building reminiscent of grand European architecture.

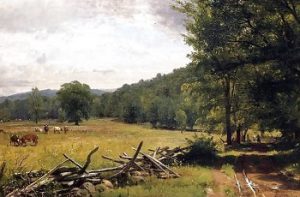

Works by an array of leading American artists, including the Hudson River School, figure and portrait painting, American impressionism represented at the display a variety of nineteenth-century tastes in painting:

Cecilia Beaux

Thomas Eakins

Theodore Robinson

Worthington Whittredge

Among American sculptors who showed their works were the prominent New York artists Daniel Chester French and Frederick MacMonnies.

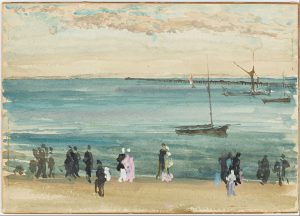

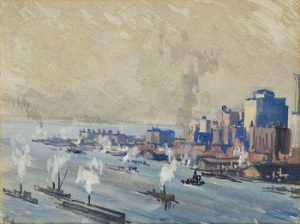

Drawings on loan to the exhibition from the Century Company in New York included works by Edwin Howland Blashfield and Kenyon Cox, both known for their beautifully drawn figures, and Howard Pyle, revered for his book illustrations. Frederick Keppeland Company, a gallery in New York that promoted the revival of etching as an original art form, loaned prints by pioneers and leaders of the etching revival movement, including city and landscape views by Seymour Haden, Charles Meryon, Joseph Pennell, and James Abbott McNeil Whistler.

Edwin Howland Blashfield

James Abbott McNeil Whistler

Joseph Pennell

The exposition seemed to spur the development of art and art activities in Atlanta, already a city of numerous studio art classes, small art schools, and exhibitions. Indeed, many enthusiasts in the capital city saw art as a great refining influence upon its citizens.

By 1900, there were renewed calls for a larger, permanent art school in Atlanta, one that would both contribute significantly to the training of artists in the South and encourage local support. Most artists in Atlanta and the state who were determined to pursue professional careers during this period traveled to Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; or European cities to further their training.

Finally, with great enthusiasm for promoting an aesthetic culture in the city, the Atlanta Art Association was officially established in 1905. Exhibitions would be an important part of its activities, and its end purpose was to found an art museum and art school.

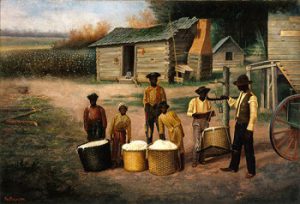

Around 1900, painting in Atlanta was still dominated by portraits and still lifes, though landscape had become a major theme in southern painting by this time.

Among leading artists of these years was painter Hal Alexander Courtney Morrison who studied art in Europe and executed skilled scenes of southern life and paintings of still life. He lived in Atlanta until 1918, teaching painting in his studio.

Lucy M. Thompson and Lucy May Stanton both painted portrait miniatures, that is, very small portraits painted on ivory.

By around 1906, Lucy May Stanton had developed a new technique of miniature painting called “puddling,” which involved the application of watercolors on ivory in a loose, impressionistic, watery manner very different from the traditional fashion of stippling (dotting), which required either small touches of paint or hatched strokes on the ivory.

Stanton’s Self Portrait: The Silver Goblet (1912–15) offers one example of her puddling technique.

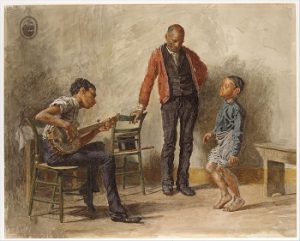

Her innovative, expanded range of subjects included portraits of everyday workers, including African Americans and southern mountaineers, as well as scenes of Black southerners at work and rest, as seen in her Churning (1910) and Working on the Street (1921), which is housed at Emory University’s Robert W. Woodruff Library.

In 1915 at Stone Mountain, the academically trained and nationally known sculptor Gutzon Borglum who later created the Mount Rushmore Memorial in South Dakota, began preliminary work on his much-publicized memorial to the Confederacy.

Borglum envisioned an expansive relief of Confederate heroes chiseled on the face of the monumental granite hill, which rises a thousand feet into the air east of Atlanta.

By Alex Arlander | ENC News