George Catlin and His Indian Gallery: A Hymn to Native American Cultures

“If my life be spared, nothing shall stop me from visiting every nation of Indians on the continent of North America.” — George Catlin.

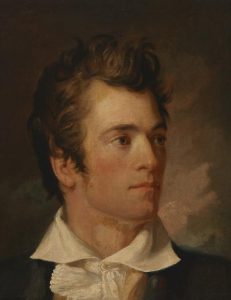

George Catlin (1796-1872) was born in the east coast city of Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania. A lawyer turned artist, he discovered his life’s work after seeing a delegation of Native Americans in the city of Philadelphia. He was determined to go out and paint the Indians in their own territory, to collect artifacts, to record the features of the Indians, to memorialize their looks.

George Catlin was the first major artist to travel beyond the Mississippi to record what he called the “manner and customs” of American Indians, painting scenes and portraits from life. He wanted to document these native cultures before they were irrevocably altered by settlement of the frontier and the mass migrations forced by the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

Between 1830 and 1836, Catlin took five trips across the Great Plains, eventually visiting fifty tribes. The nearly complete surviving set of Catlin’s first Indian Gallery, painted in the 1830s, constitutes more than five hundred works.

George Catlin’s Indian Gallery is an unparalleled collection of great artistic and historic significance that contributes to understanding America’s frontier and the cultures of the Native Americans who lived there.

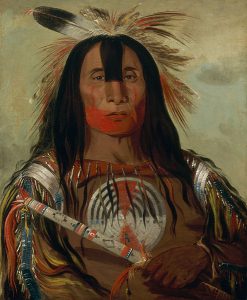

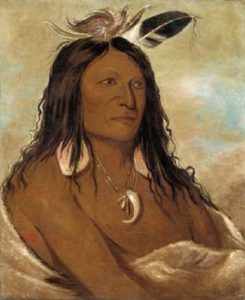

Stu-mick-o-súcks, Buffalo Bull’s Back Fat, Head Chief, Blood Tribe, 1832.

This magnificent portrait was painted at Fort Union “from the free and vivid realities of life” rather than “the haggard deformities and distortions of disease and death” that George Catlin noted among frontier Indians. Buffalo Bull’s Back Fat (named after a prized cut of bison) was a chief of the Blackfoot, a tribe of the northernmost Plains whose territory straddled the present-day border between the United States and Canada. Catlin considered the people of the northern Plains the least corrupted by white contact, and he helped establish their image as nature’s noble people in Europe as well as America. This commanding portrait, for example, was exhibited to favorable notice in the Paris Salon of 1846.

Eé-shah-kó-nee, Bow and Quiver, First Chief of the Tribe, 1834.

George Catlin described this Comanche chief as “pleasant looking . . . without anything striking or peculiar in his looks; dressed in a very humble manner . . . his hair carelessly falling about his face, and over his shoulders.” He noted that “the only ornaments to be seen about him were a couple of beautiful shells worn in his ears, and a boar’s tusk attached to his neck, and worn on his breast.” The chief’s mild demeanor masks the ferocious struggle against white settlers that his people would sustain for decades.

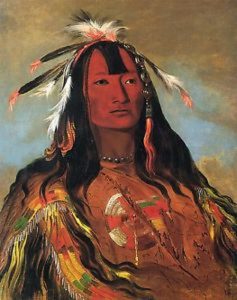

Hee-oh’ks-te-kin, Rabbit’s Skin Leggings, 1832

George Catlin probably painted this portrait of Hee-oh’ks-te-kin in St. Louis, or aboard the steamboat Yellowstone, in 1832. The dignified bearing of the young men and the attention to detail in the elaborately beaded tunics and beaded and feathered hair reflect Catlin’s regard for his subjects. Native Americans, he wrote, were “the finest models in all Nature, unmasked and moving in all their grace and beauty.” Catlin’s faithful effort to document the life of these peoples in the early nineteenth century captures those impressive cultures as they were before their world was shattered.

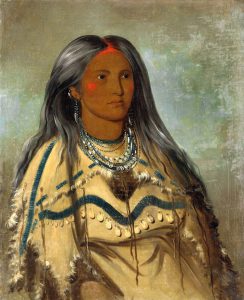

Sha-kó-ka, Mint, a Pretty Girl, 1832

“A very pretty and modest girl,” George Catlin wrote, “twelve years of age, with grey hair! peculiar to the Mandans . . . There are very many, of both sexes, and of every age, from infancy to manhood and old age, with hair of a bright silvery grey; and in some instances almost perfectly white. This singular and eccentric appearance is much oftener seen among the women than it is with the men; for many of the latter who have it, seem ashamed of it, and artfully conceal it, by filling their hair with glue and black and red earth. The women, on the other hand, seem proud of it, and display it often in an almost incredible profusion, which spreads over their shoulders and falls as low as the knee. I have ascertained, on a careful enquiry, that this strange and unaccountable phenomenon is not the result of disease or habit; but that it is unquestionably a hereditary character which runs in families, and indicates no inequality in disposition or intellect. And by passing this hair through my hands, as I often have, I have found it uniformly to be as coarse and harsh as a horse’s mane; differing materially from the hair of other colours, which amongst the Mandans, is generally as fine and as soft as silk.” Catlin painted Sha-kó-ka at a Mandan village in 1832

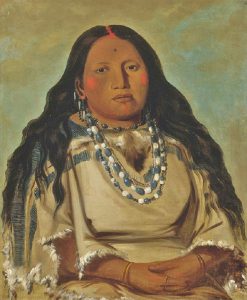

Kah-beck-a, The Twin, Wife of Bloody Hand, 1832

The Twin was the wife of Bloody Hand, chief of the Arikara tribe. George Catlin painted both their portraits during his travels West in 1832. This portrait was painted at a Mandan village.

Káh-kée-tsee, Thighs, a Wichita Woman, 1834

“Amongst the women of this tribe, there were many that were exceedingly pretty in feature and in form; and also in expression, though their skins are very dark . . . They are always decently and comfortably clad, being covered generally with a gown or slip, that reaches from the chin quite down to the ankles, made of deer or elk skins . . . I have given the portraits of . . . [Thighs and Wild Sage], the two . . . women who had been held as prisoners by the Osages, and purchased by the Indian Commissioner, the Reverend Mr. Schemmerhom, and brought home to their own people.” Catlin probably painted this portrait at Fort Gibson (in present-day Oklahoma) in 1834.

George Catlin developed great respect for the Indians in the course of his travels, and he mourned a way of life that seemed to be vanishing as quickly as he could reproduce it. The artist captured that loss in his double portrait of an Indian chief he met named “Pigeon’s Egg Head.”

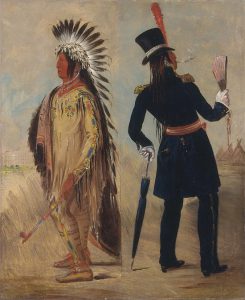

Wi-jún-jon, Pigeon’s Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington, 1837-1839.

Catlin mistranslated Ah-jon-jon, whose name means “The Light,” as “Pigeon’s Egg Head.” The Light was an Assiniboine leader who was invited in 1831 to represent his tribe in Washington. During a winter in the nation’s capital, he traded his native dress for European clothes and customs. In Catlin’s before-and-after portrait, the once proud warrior, with a liquor bottle in his pocket, swaggers in high-heeled boots and carries a fan and umbrella. For Catlin, this transformation illustrated the tragic gulf between Native American and white cultures.

George Catlin first met the Light in St. Louis in December 1831, when the Assiniboine warrior was en route to Washington to meet President Andrew Jackson and tour the city. Catlin recalled that the warrior appeared for his portrait sitting “plumed and tinted . . . and dressed in his native costume, which was classic and exceedingly beautiful.” Wi-jún-jon returned home to the northern Plains eighteen months later a decidedly different man—dressed apparently in a “general’s” uniform and sharing what to his fellow tribesmen were astonishing accounts of the white man’s cities. They eventually rejected his stories as “ingenious fabrication of novelty and wonder,” and his persistence in telling such “lies” eventually led to his murder. The people thought he was a wizard, he was evil, and so some brave man killed him.

Buffalo Chase with Bows and Lances, 1832-1833

Of Buffalo Chase, George Catlin wrote: “I have represented a party of Indians in chase of a herd, some of whom are pursuing with lance and others with bows and arrows. George Catlin sketched this scene on the Upper Missouri.

George Catlin is considered an early proponent of wilderness conservation and the national park idea. His advocacy remains relevant today—to the Great Plains, the buffalo, and land use.

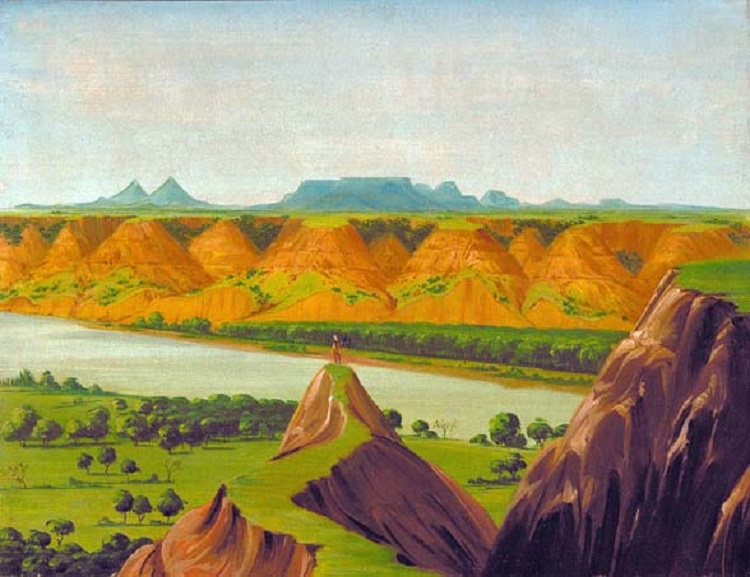

Mouth of the Platte River, 900 Miles above St. Louis, 1832

“The mouth of the Platte,” George Catlin wrote, “is a beautiful scene, and no doubt will be the site of a large and flourishing town, soon after the Indian titles shall have been extinguished to the lands in these regions . . . The Platte is a long and powerful stream, pouring in from the Rocky Mountains.” The artist painted this work in 1832 on his first extended voyage up the Missouri River.

An amateur geologist

Catlin responded to the landscape as both a painter and an explorer. When he got further up the Mississippi he started to find that the stratification of the landscape was very interesting. And he was something of an amateur geologist. When he went to Pipestone, he realized the stone there the Indians quarried for their peace pipes was a very different looking kind of stone. And so he brought it back and the geologists looked at it and said, this is like nothing we’ve ever seen before, and the stone was named ‘Catlin.‘”

George Catlin’s last years were difficult. When he started including live Indian performances in his traveling shows, he was accused of exploitation. He also faced financial problems so severe that he finally had to sell his paintings to industrialist Joseph Harrison. Catlin tried unsuccessfully to get the Smithsonian to buy the collection before his death in 1872. “His dying words were, ‘What will happen to my Indian gallery?’ And as it turned out in 1878 the widow of Joseph Harrison said to the next Secretary of the Smithsonian, ‘If you have a place to exhibit this, I will give them to you.’

George Catlin’s paintings inspire us

“If it were not for George Catlin, many of us tribes would have lost many things. You see the tribal designs, the paints, the proudness of the people that he sketched, and it just inspires me so much.” – Merle Tendoy, a Native American.