“There is more done with pens than with swords”, Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811 – 1896)

For more than 170 years, the fame of the world-recognized American writer and philanthropist Harriet Beecher Stowe has not faded. Her works, filled with endless love for people and uncompromising truth, continue to live among us and inspire generations to do deeds of kindness, justice and mercy.

Her wise thoughts about the meaning of human life became maxims. They are widely cited and serve as a guide for those seeking to live in peace with themselves and others, regardless of their religious, political, and racial differences.

Here are just a few of them. They encourage the soul in despair, calm the heart and fill it with compassion and mercy for others, instill firm faith that truth and kindness always win.

“When you get into a tight place, and everything goes against you till it seems as if you could n’t hold on a minute longer, never give up then, for that’s just the place and time that the tide’ll turn.”

“The truth is the kindest thing we can give folks in the end.”

“Any mind that is capable of real sorrow is capable of good.”

“The pain of discipline is short, but the glory of the fruition is eternal.”

“It’s a matter of taking the side of the weak against the strong, something the best people have always done.”

“Once in an age God sends to some of us a friend who loves in us, not a false-imagining, an unreal character, but looking through the rubbish of our imperfections, loves in us the divine ideal of our nature, loves not the man that we are, but the angel that we may be.”

“Many a humble soul will be amazed to find that the seed it sowed in weakness, in the dust of daily life, has blossomed into immortal flowers under the eye of the Lord.”

“It takes years and maturity to make the discovery that the power of faith is nobler than the power of doubt; and that there is a celestial wisdom in the ingenuous propensity to trust, which belongs to honest and noble natures.”

“The past, the present and the future are really one: they are today.”

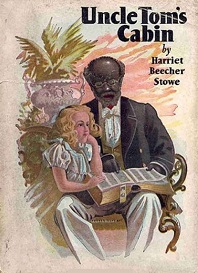

Harriet Beecher Stowe, née Harriet Elizabeth Beecher, was born June 14, 1811, Litchfield, Connecticut, U.S. and died July 1, 1896, Hartford, Connecticut. She is the author of the world-known novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which contributed so much to popular feeling against slavery and was cited among the causes of the American Civil War.

Harriet Beecher was a member of one of the 19th century’s most remarkable families. The daughter of the prominent Congregationalist minister Lyman Beecher and the sister of Catharine, Henry Ward, and Edward, she grew up in an atmosphere of learning and moral earnestness.

She believed that the most important character trait anyone can possess, is a strong sense of duty to conscience. Such a conscience that commands a person or nation to obey the Highest Law.

She believed that humanity was created under the “dominion of conscience” and that once the people were enlightened they must surely be compelled to do that which was right.

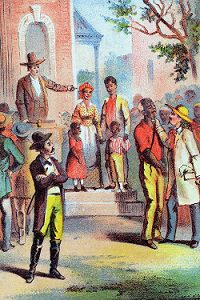

Firmly believing in that Abolition was an imperative ordained by our Creator, with a heart full of grief and empathy she set pen to paper and wrote the best-selling book of the 19th century Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

From 1832 to 1850 she lived in Cincinnati, which was separated only by the Ohio River from a slave-holding community. She came in contact with fugitive slaves and learned about life in the South from friends and from her own visits there.

In 1850 Harriet’s husband Calvin Ellis Stowe, a seminary professor and an eminent biblical scholar, became professor at Bowdoin College and the family moved to Brunswick, Maine.

Calvin Ellis Stowe encouraged the literary activity of his wife.

In Brunswick, Harriet Stowe began to write a long tale of slavery, based on her reading of abolitionist literature and on her personal observations in Ohio and Kentucky.

Her tale was published serially (1851–52) in the National Era, an antislavery paper of Washington, D.C.

In 1852 it appeared in book form as Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly.

Its original title, according to an announcement in the May 8, 1851 issue of the National Era was Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or the Man that was a Thing. But one month later, on June 5, 1851, the title was slightly modified to Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly.

The book was an immediate sensation and was taken up eagerly by abolitionists while, along with its author, it was vehemently denounced in the South, where reading or possessing the book became an extremely dangerous enterprise.

With sales of 300,000 in the first year, the book exerted an influence equaled by few other novels in history, helping to solidify both pro- and antislavery sentiment.

The book was translated widely and several times dramatized, where it played to capacity audiences.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought Stowe instant fame, but also angered many in the South. According to the Philadelphia Times, “Mrs. Stowe was for a time the most hated woman in the United States.” (March 9, 1887.)

Stowe was enthusiastically received on a visit to England in 1853, and there she formed friendships with many leading literary figures.

In that same year she published A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a compilation of documents and testimonies in support of disputed details of her indictment of slavery.

In 1856 she published Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, in which she depicted the deterioration of a society resting on a slave basis.

When The Atlantic Monthly was established the following year, she found a ready vehicle for her writings; she also found outlets in the Independent of New York City and later the Christian Union, of which papers her brother Henry Ward Beecher was editor.

Once, during Tea with President Lincoln in 1862, Harriet Beecher Stowe seemed to recall him saying something to the effect of “So you are the little lady that wrote the book that caused this Great War.”

He was referring to her epic work Uncle Tom’s Cabin published a decade earlier.

When Harriet Beecher Stowe was asked to comment on her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she said, “It is no merit in the sorrowful that they weep, or to the oppressed and smothering that they grasp and struggle, nor to me, that I must speak for the oppressed who cannot speak for themselves. I hoped by such means as a lady may use, to do something to promote a good understanding among all the enemies of slavery…when a higher being has purposes to be accomplished he can make even a grain of mustard seed the means.”

Contemporaries who knew her closely said, “A meeting with Harriet Beecher Stowe is like spending time with the best friend with whom you can share your most ardent desires for a better world, the dear aunt that you could always rely upon for sound advice, and the beloved mother you could always count on to kiss your wounds and make them feel better.”

By Alex Arlander | ENC News