“I Wrote This Book Because I Love You”

Writer and cartoonist Tim Kreider speaks about his new book of nonfiction essays about women he has known called “I Wrote This Book Because I Love You”.It’s a series of essays about some of the women he’s known – old girlfriends, his elderly cat, former students, even the psychologist who tested him when he was a baby. The author believes he had a problem with making relationships last. But the essays are not the work of a nebbish who finds laughs in his romantic floundering, though he often does

Do you think you have a problem you’d like to work out, or are you just as happy to keep that problem around, so you can have great material?

Kreider: You know, it’s sort of a romantic or adolescent notion to cherish your problems as motivation or material. As a person, I am trying to get over the same dumb problems that keep thwarting me. But I feel like writing about oneself is such an embarrassingly indulgent thing to do that you’d better justify it somehow. And in my case the rule of thumb is there had better be more in it for the reader than for you.

Say some words about the people and personalities of the book.You once pretended to be married to Annie – a woman named Annie – to ride a circus train.

Kreider: Yes, it was necessary to impersonate her spouse in order to be allowed to ride the circus train. She was then working as a teacher for the children of circus performers, and she wanted me to go with her to Mexico City as protection. She was very nervous about it.It was one of the only totally successful relationships I’ve ever had.

You suggest there are some relationships that can be successful in motion, but none the less they end.

Kreider: Yes, of course. Besides, I think that I’m only responsible for half of what’s in that essay. You’re responsible for the other half.

You were part of a childhood study at Johns Hopkins.

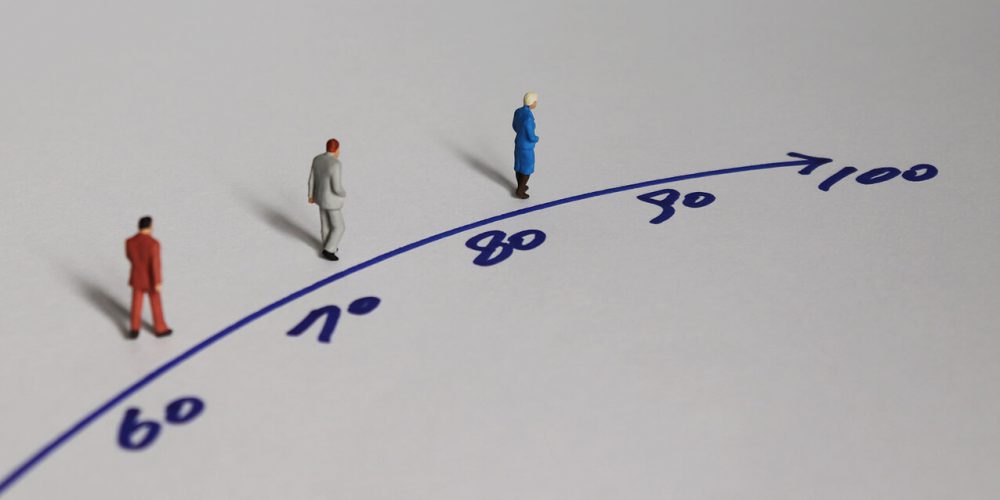

Kreider: Yes. That was what became a seminal study in child development in attachment theory. It was called”The Strange Situation”. Basically, it’s become the go-to lab setup for determining a child’s attachment style or pattern.

You enlisted the help of Margot, a science reporter, and actually were able to establish contact with the doctor.

Kreider: Margot was invaluable. She was also a close friend of mine. And so she had a certain interest in the study and some inside knowledge about me.

And what do you think you discovered with this dive into the data with the youngster who used to be you?

Kreider: I would say if I came around to any conclusion for myself, it was about free will. My position is, technically, we do, but we almost never exercise it. It’s so hard to overcome our instincts and our pasts and our conditioning. It requires a lot of insight and effort that we’re usually not willing to make unless things have gotten really bad.

In one of the essays there is a sentence “like a lot of unhappy people, I had formed a half conscious assumption that unhappiness was a function of intelligence”. Do you still feel that way?

Kreider: No, I don’t. I don’t romanticize unhappiness anymore. I used to. I think that’s an adolescent notion. You know, you tend to believe that whatever is dark or misanthropic or pessimistic is necessarily truer than anything affirmative. And I think it’s harder to find your way through recognition of what the world is like and what kind of human beings are to some sort of equanimity, if not hope.

You’ve written a beautiful book. You have a lot to be proud of. You have a rich life. Are you happy?

Kreider: (Smiling) It depends when you ask. Some days. I will say that, you know, I don’t think you write for therapy. But I found it to be true that while I’ve been in the middle of writing both my books of essays, I found it just about impossible to go out with anybody. I just did not have the emotional energy to commit to it or the attention or something. And also, I think I was just working through very naughty problems. Now that I’m finished this book, I am in a happy relationship. I don’t know if we would attribute that to the book, but things are better.